Canada won the trade panel. The U.S. has the sunset clause. July 2026 decides who blinks first in the $850M dairy standoff.

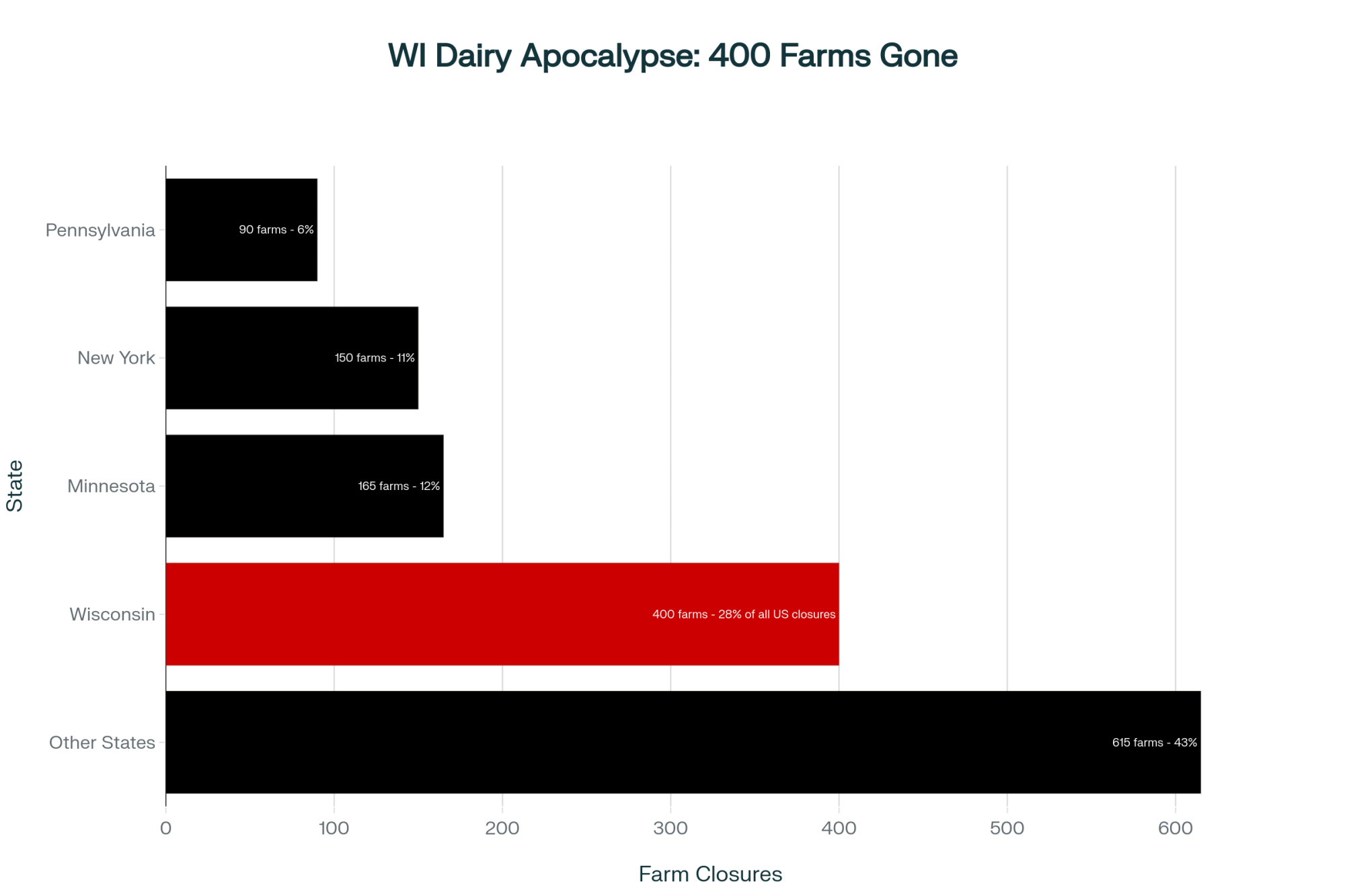

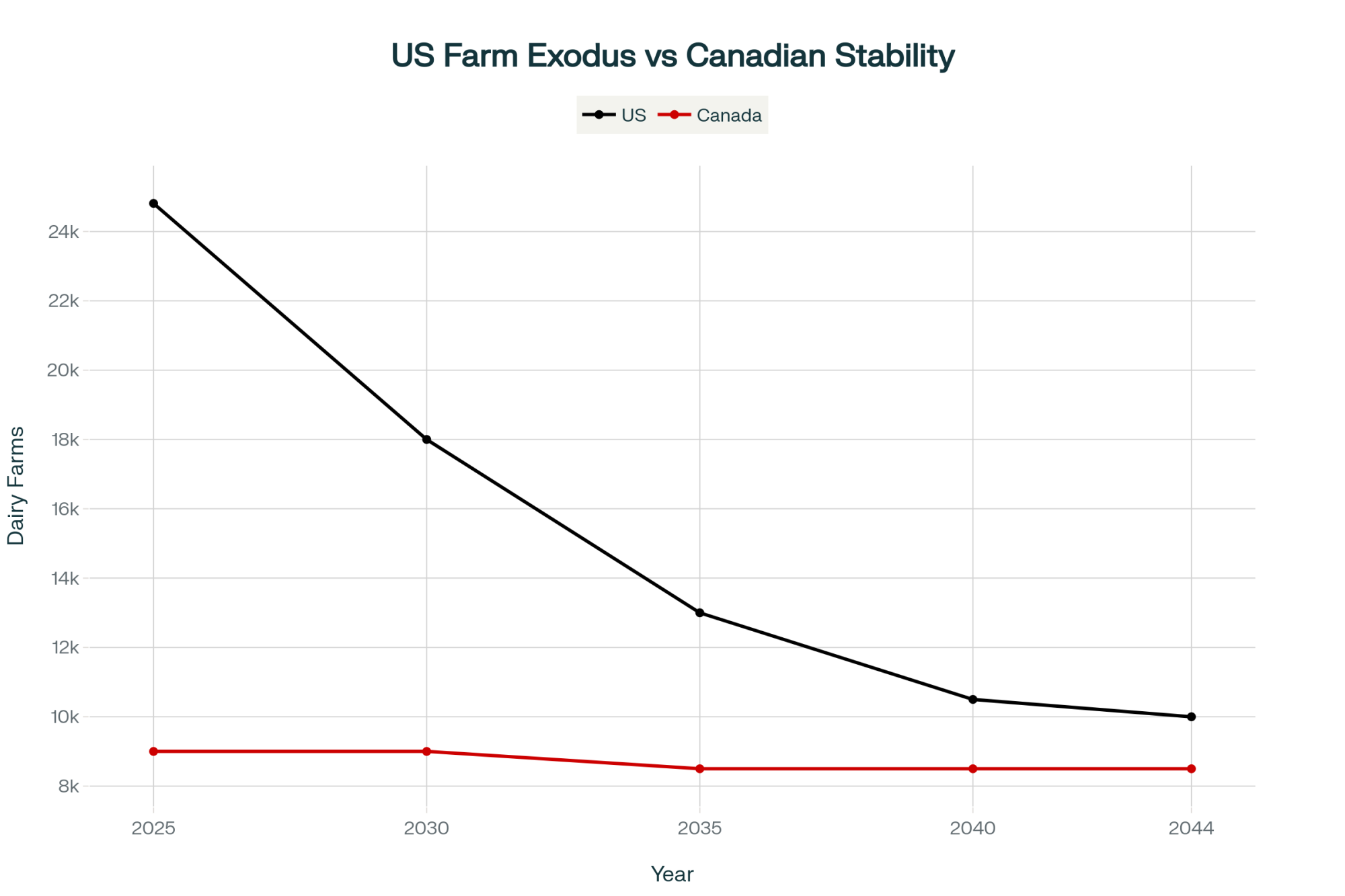

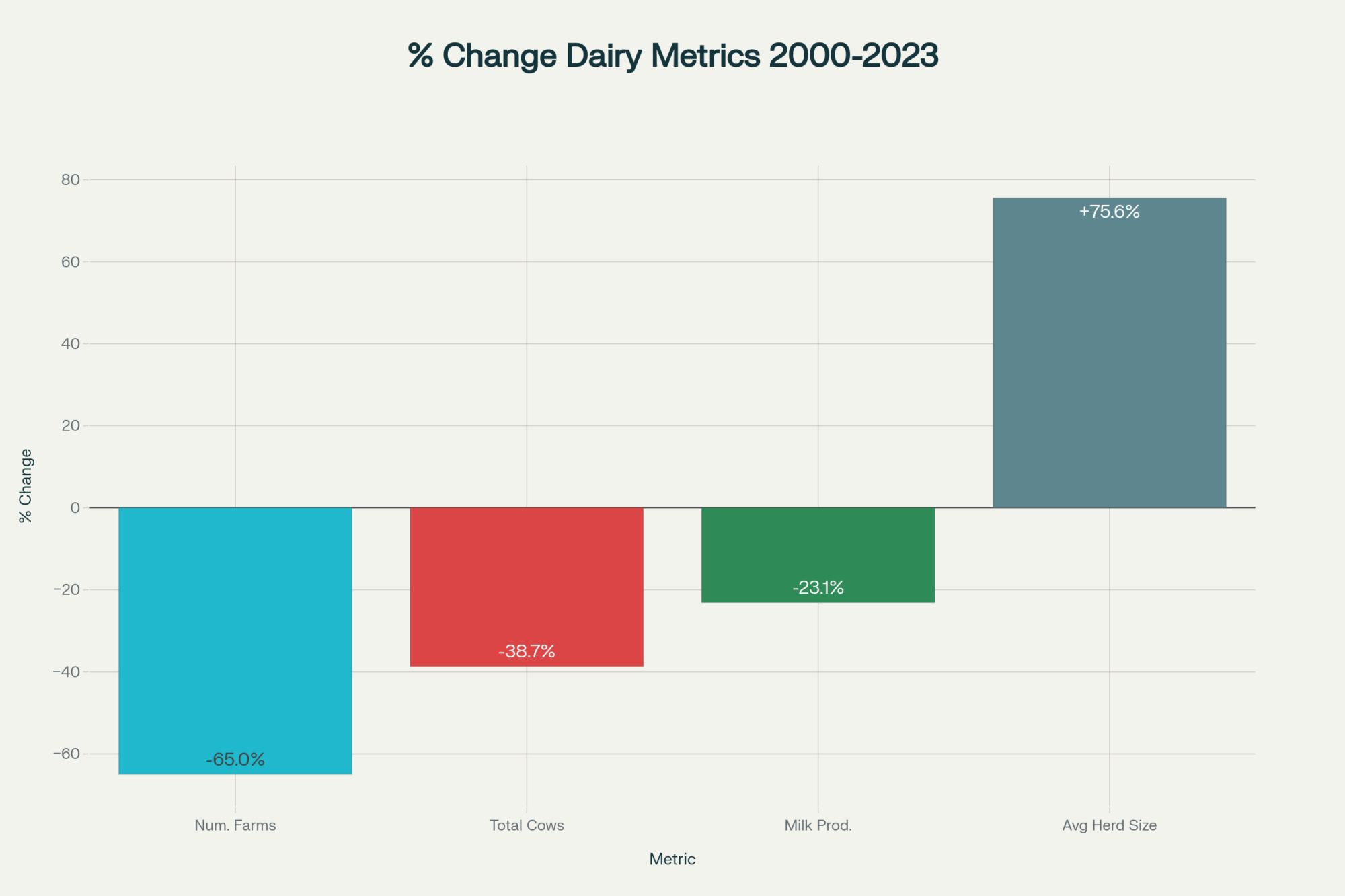

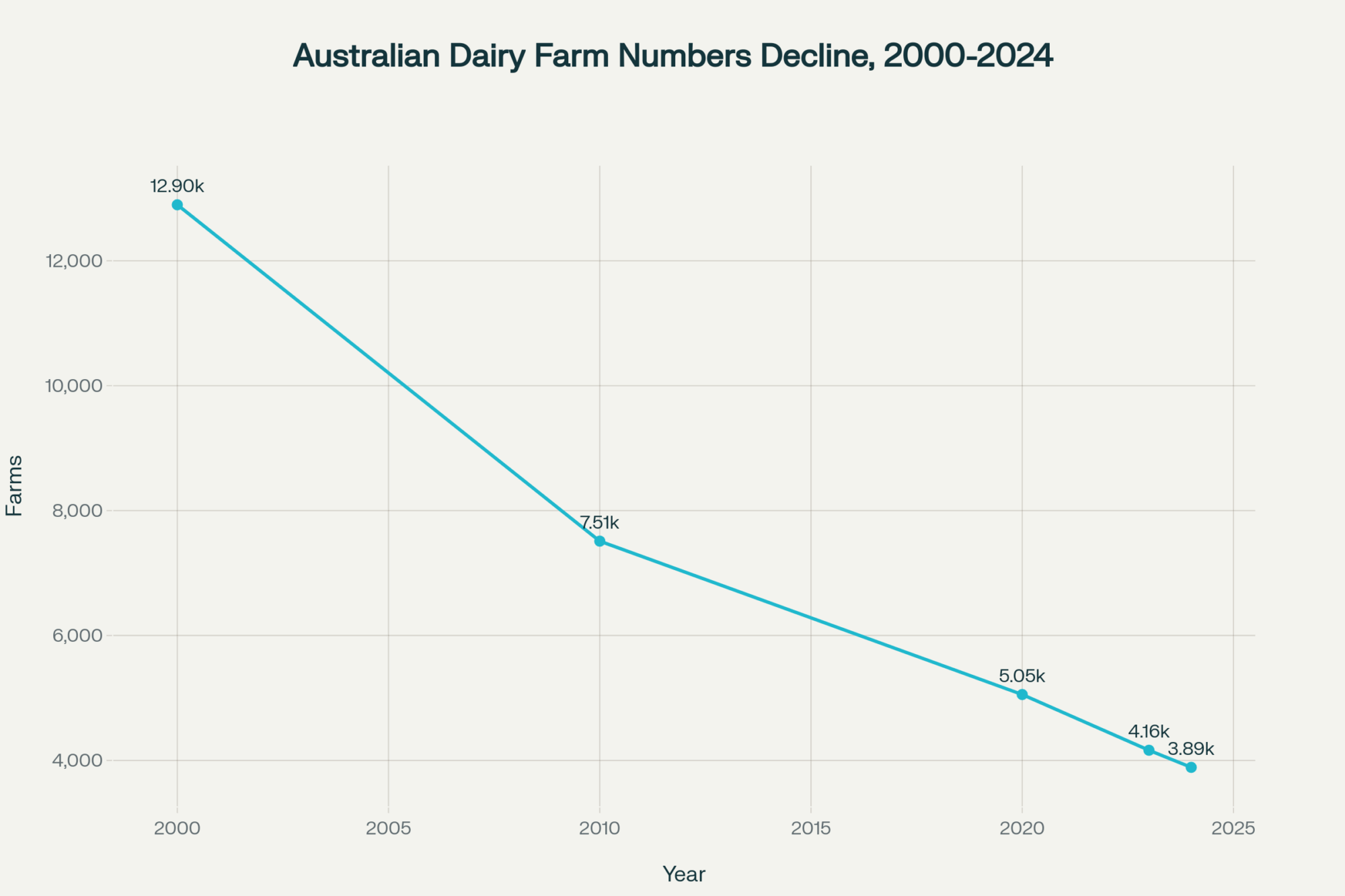

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Wisconsin dairy farmers are asking a simple question: Where’s the Canadian market access USMCA promised five years ago? The U.S. industry says Canada blocked $850 million in opportunities by allocating import quotas to processors who won’t use them, keeping fill rates at just 42%. Canada counters they’re following the rules—winning a November 2023 panel to prove it—and argues American dairy simply isn’t competitive in their market. With 1,420 U.S. farms closing last year while Canadian producers protect quota investments worth $30,000 per cow, both sides face existential stakes. July 2026 changes everything: the USMCA sunset clause means all three countries must actively agree to continue, or $780 billion in annual trade enters dangerous uncertainty. This analysis presents both perspectives fairly and provides specific strategies based on your farm size—because regardless of who “wins,” every North American dairy operation needs to prepare for what comes next.

As we approach the July 2026 USMCA review, the U.S. dairy industry is building their case while Canada defends its position. Here’s what both sides are saying—and why it matters for dairy farmers across North America.

You know what’s interesting? When you talk to Wisconsin producers these days, there’s this deep frustration that just keeps coming up. Five years after the USMCA promised meaningful Canadian market access, they’re still waiting. And it’s not just Wisconsin—this sentiment’s spreading across the entire U.S. dairy belt, setting up what could be quite a showdown come July 2026.

So here’s what’s happening. The International Dairy Foods Association filed this formal complaint in October to the Trade Representative, and when you combine that with five years of trade data from both USDA and Canada’s Global Affairs department… well, the U.S. industry’s making a pretty specific case. They’re talking about roughly $850 million in export opportunities that haven’t materialized, all while 1,420 American dairy operations shut down last year, according to the USDA’s count.

But here’s the thing—and this is important—Canada sees this completely differently. They won that November 2023 dispute panel, and they’re saying they’re following the agreement just fine. Understanding both perspectives has become essential for anyone trying to make sense of what’s coming.

What the U.S. Industry Says Was Promised vs. What They Got

Let me walk you through the American dairy sector’s position. It starts with the International Trade Commission’s 2019 assessment, which projected we’d see about $227 million in additional annual exports under USMCA’s dairy provisions.

The way U.S. producers see it, they were expecting:

- Access to 3.6% of Canada’s dairy market through 14 different quota categories

- Complete elimination of those Class 6 and 7 pricing schemes within six months

- Export caps keeping Canadian skim milk powder and milk protein concentrates at 35,000 metric tons annually

- Import quotas going to actual importers, not Canadian processors

Now, according to Canada’s own Global Affairs data and those USMCA panel findings, what actually happened looks quite different.

What were the average quota fill rates from 2022 to 2023? Just 42% across all categories. Nine of those 14 categories never even hit 50% utilization. And that January 2022 USMCA panel—they found that Canada had allocated between 85% and 100% of its quota shares to Canadian processors. American farmers argue these processors have about as much incentive to import competing U.S. products as… well, let’s just say not much.

Here’s what really gets American producers going—this Class 7 pricing business. Sure, Canada technically eliminated it like they promised. But then—and the University of Wisconsin’s dairy economists have documented this—similar pricing dynamics popped up under Class 4a. The U.S. sees that as a way to get around its USMCA commitments.

“You get on a phone conversation with some of these folks that have been farming for five and six generations. How do you say I can’t help you? That becomes very tough.” – Bill Mullins, Mullins Cheese

Quick Reference: Understanding Key Trade Terms

TRQ (Tariff Rate Quota): Think of it as a two-tier system. A certain amount gets in at low or zero tariffs. Above that? You’re looking at 200-315% tariffs for Canadian dairy.

Supply Management: Canada’s comprehensive dairy system since 1972—combines production quotas, price supports, and import controls.

Class Pricing: Canada’s milk classification system that sets different prices based on how the milk’s used—and this is where things get contentious.

Why Canada Defends Supply Management So Fiercely

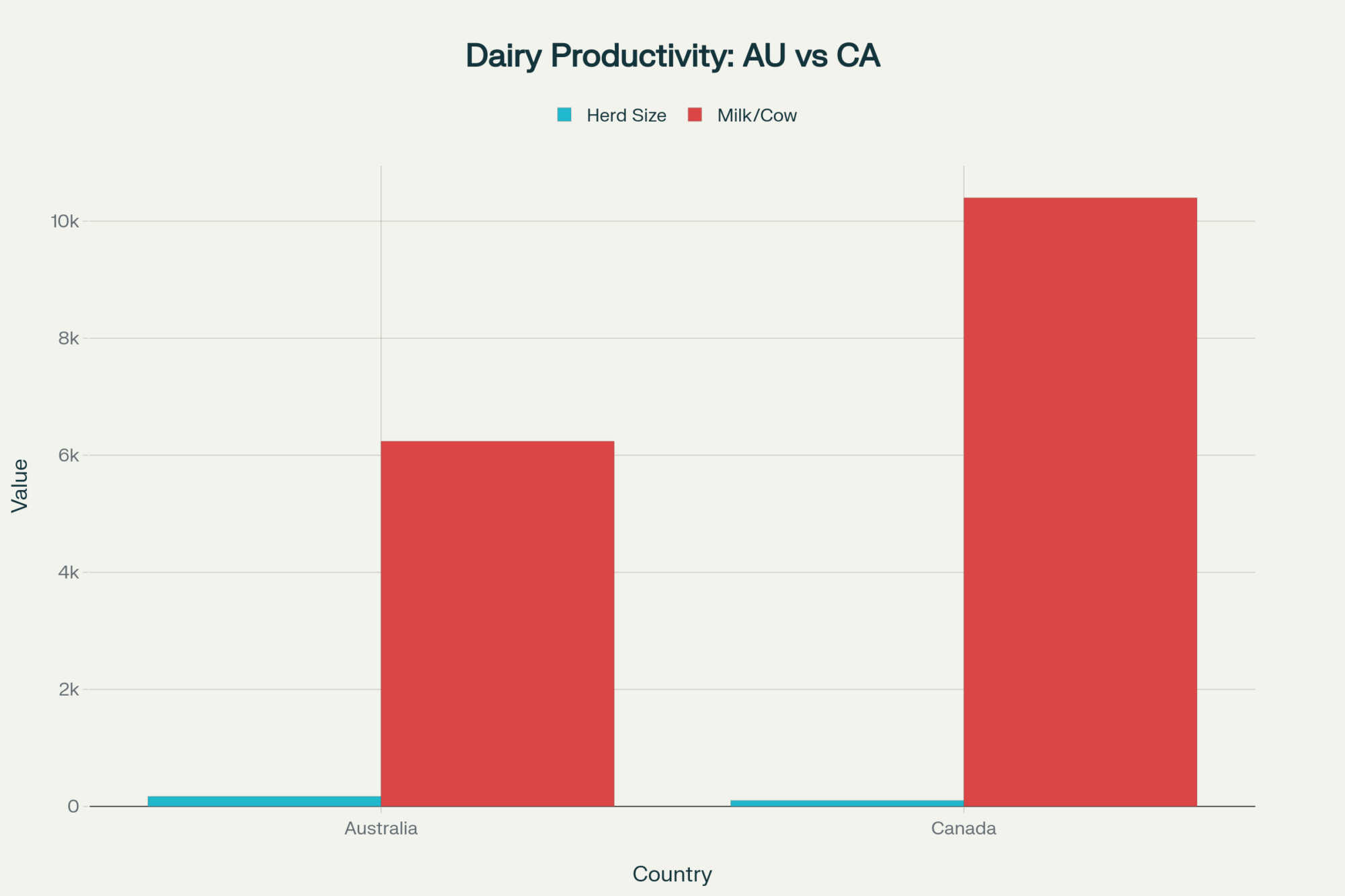

You know, when you really look at Canada’s dairy system, you start to understand why they’re so protective of it. Agricultural economists at Université Laval have documented how it works through three integrated pieces:

First, there’s production quotas that limit what each farmer can produce. Then you’ve got price supports keeping farmgate values at about 1.5 to 2 times what we see in the U.S. And finally, those import barriers—we’re talking 200% to 315% on anything over quota.

This whole framework’s supporting about 9,000 Canadian dairy operations that generate close to CA$20 billion in annual economic activity, according to Dairy Farmers of Canada’s latest report.

Mark Stephenson over at UW-Madison’s dairy policy program explains it well: “The fundamental incompatibility is that supply management requires import control to function. Asking Canada to provide meaningful market access is essentially asking them to dismantle the system piece by piece. From their perspective, that’s existential.”

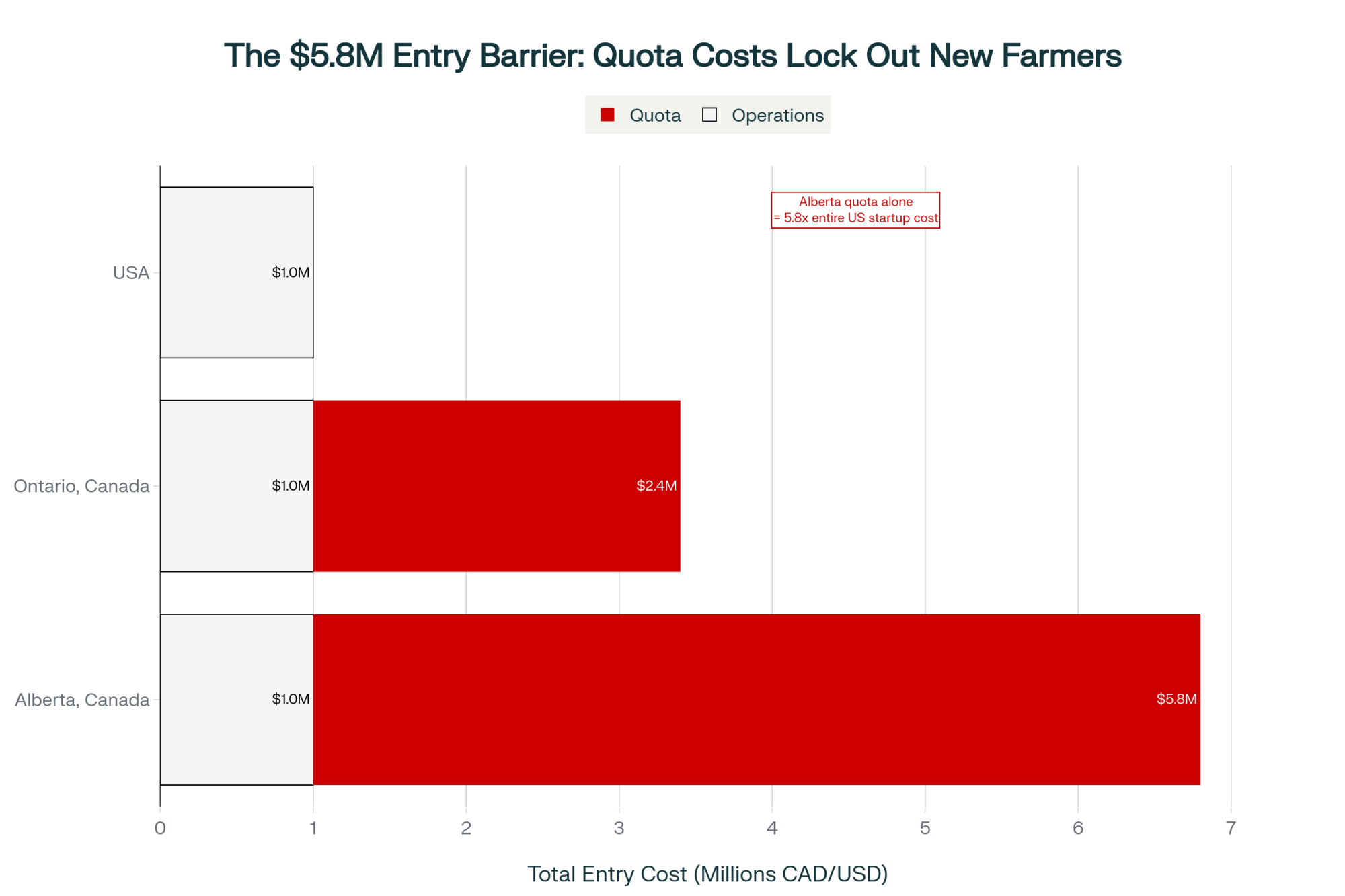

And here’s something to consider—Canadian producers have invested around CA$30,000 per cow in quota value according to their provincial milk boards. That’s not just an operating expense. That’s retirement savings, succession planning, and their kids’ inheritance. No wonder they defend it so fiercely.

How American Farmers See the Economic Stakes

For U.S. producers, the Grassland Dairy situation from 2017 is still a really raw issue. It kind of exemplifies their broader concerns about Canadian trade practices.

When Canada introduced that Class 7 pricing targeting ultra-filtered milk, Grassland Dairy had to terminate contracts affecting about a million pounds of daily production across 75 Wisconsin farms. Bill Mullins from Mullins Cheese—he took on eight of those displaced operations even though his plants were already near capacity. His words still resonate.

Here’s what keeps U.S. producers up at night:

Wisconsin Center for Dairy Profitability data shows your average 200-cow operation generates about $87,000 in annual net income. If you lost $56,000 in potential export revenue—that’d be each farm’s theoretical share of that $850 million—you’re looking at a 64% income hit.

The numbers that really worry them:

- Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies jumped 55% in 2024, hitting 259 filings

- Wisconsin dairy operations averaged just $0.87 per hundredweight in net margins during 2023

- At those margins, farms facing reduced market access could hit insolvency within 30 months

New York dairy producers have been pretty vocal about their frustration, arguing they’re seeking the market access they were promised, not handouts. One Cayuga County operator mentioned how expansion decisions are basically on hold until there’s clarity about Canadian market availability.

Canada’s Counter-Argument: Why They Say They’re Complying

Now here’s where it gets really interesting—Canada’s perspective on USMCA compliance is fundamentally different from the U.S.’s.

First off, Canada won that November 2023 USMCA dispute panel ruling. The panel found 2-1 that Canada’s revised allocation methods based on market share didn’t violate USMCA provisions. That’s a big deal—it validated Canada’s position that their implementation, while maybe not what the U.S. expected, technically complies with the agreement.

The way Canadian officials see it, several key points counter U.S. arguments:

On those low quota fill rates, they argue this reflects market conditions and U.S. producers’ inability to meet Canadian market requirements, not administrative barriers. They say importers are free to source from the U.S. if the products are competitive.

On processor allocations: Canada maintains that allocating quotas based on historical market activity is legitimate and non-discriminatory. It doesn’t explicitly exclude any type of importer.

On Bill C-202: Rather than overplaying their hand, Canada sees that June 2025 legislation—where 262 of 313 MPs voted to prohibit dairy concessions—as a democratic expression of national consensus. All parties supported it. From their perspective, that’s sovereign policy choice, not a negotiating tactic.

Dairy Farmers of Canada has consistently maintained that supply management represents more than just an economic system—they see it as ensuring food security and stable farm incomes across rural Canada. Pierre Lampron, who served as DFC president through 2024, expressed confidence at their annual meeting that the government understands this broader context.

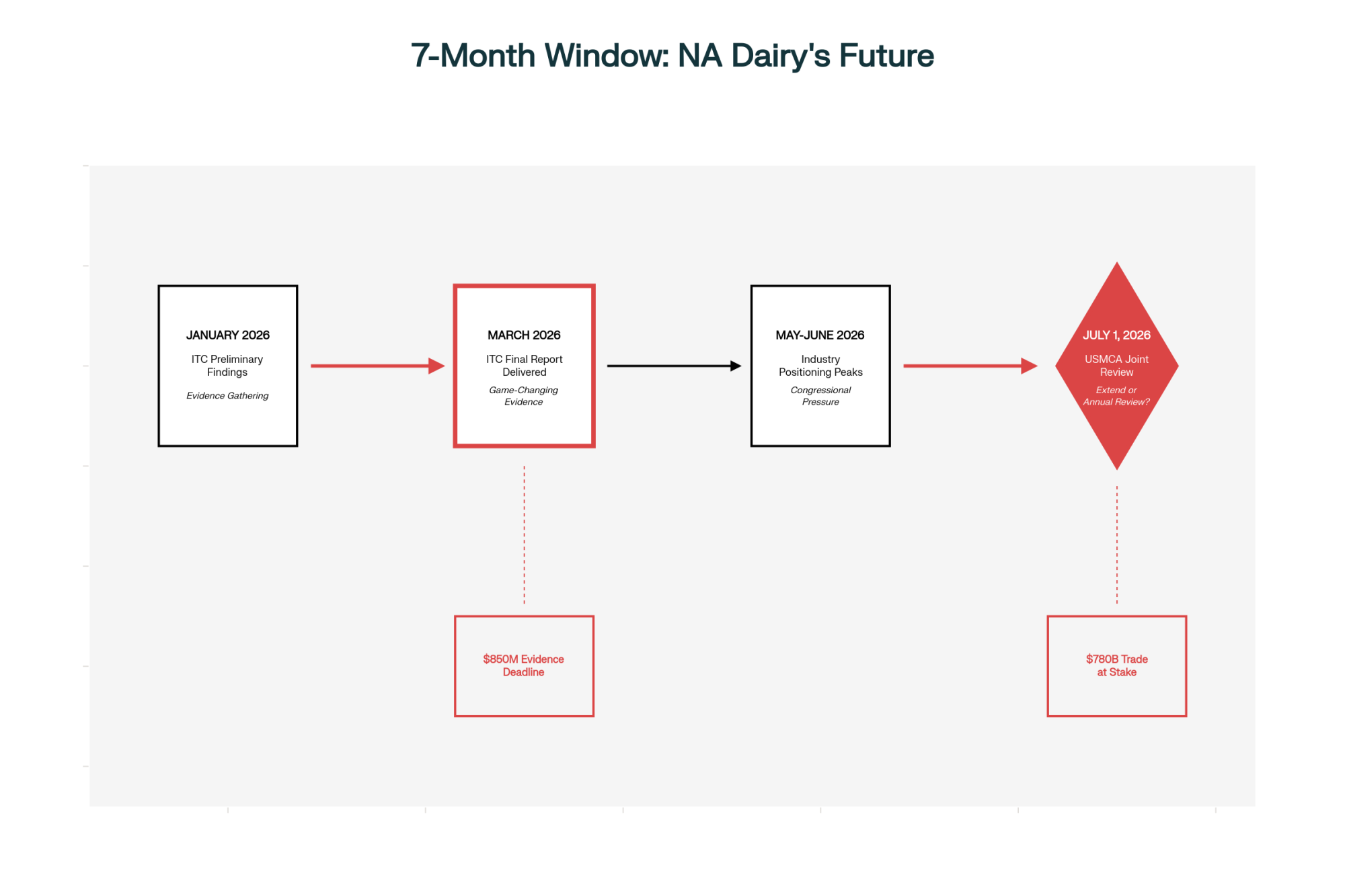

Timeline: Key Dates Leading to July 2026 Review

January 2026: Monitor for ITC preliminary findings on protein dumping investigation

March 2026: ITC final report delivers—this could be game-changing evidence

May-June 2026: Industry positioning intensifies, Congressional pressure peaks

July 1, 2026: USMCA joint review—decision on extension or annual review mode

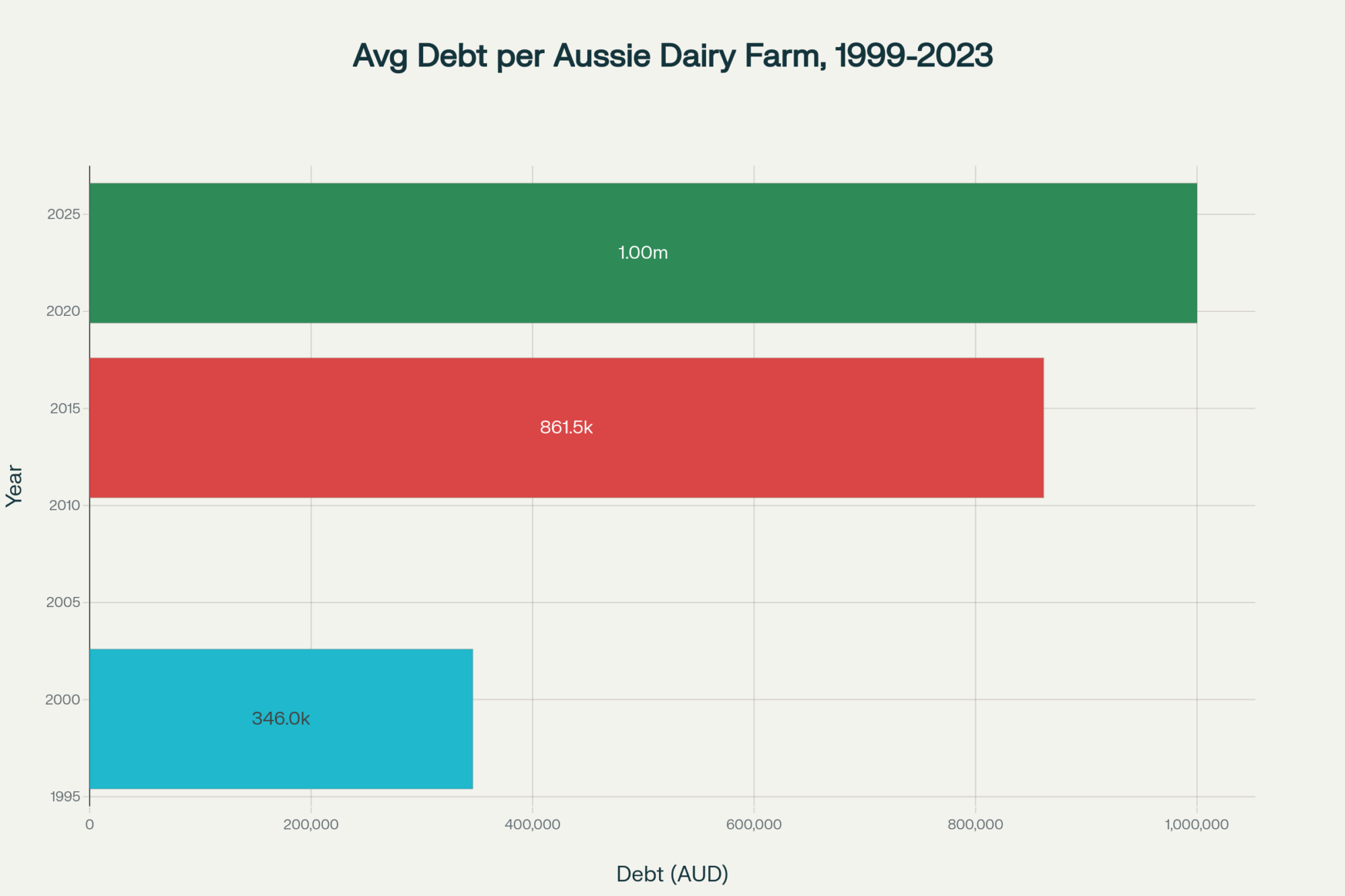

Here is the data from the image converted into a table:

Two Countries, Two Systems

| Aspect | U.S. System | Canadian System |

| Farm Closures (2024) | 1,420 operations (5% decline) | Stable/protected |

| Quota Investment per Cow | $0 | $30,000 |

| Price Stability | Volatile (market-based) | Guaranteed (1.5-2x U.S. prices) |

| Market Access Barriers | None domestically | High tariffs (200-315%) |

| Export Opportunities | Growing but constrained by Canada | Limited by supply management |

The Political Leverage Game for 2026

Both sides are positioning themselves for July 2026 with some distinct strategic advantages.

What the U.S. Industry Has Going For It

The timing of the ITC investigation is no accident. The International Trade Commission investigation into Canadian dairy protein dumping delivers findings in March 2026. That’s just four months before the review—giving U.S. negotiators the federal agency documentation they need right when they need it.

The sunset clause creates real pressure. USMCA requires all three countries to actively confirm they want to extend the agreement in July 2026. If they don’t, we’re looking at uncertainty over $780 billion in annual bilateral trade.

Congressional backing matters. Bipartisan pressure from dairy-state legislators provides the U.S. industry with political support to push enforcement demands.

Canada’s Strategic Position

Legal victories count. That November 2023 panel ruling provides Canada with legal cover for its current practices. They can say, “Look, we went through dispute settlement and won.”

Political unity is powerful. Bill C-202’s overwhelming parliamentary support shows that protecting supply management goes beyond party politics in Canada.

The broader relationship provides leverage. Canada can point to integrated North American supply chains—especially in automotive and energy—to resist dairy-specific pressure.

Three Scenarios and What They Mean for Different Farm Sizes

Looking at how things are shaping up, here’s what seems most likely and what it means for your operation:

Scenario 1: More Incremental Changes (45% probability, if you ask me)

Canada agrees to better reporting and maybe some monitoring mechanisms, but keeps its fundamental allocation approaches. The U.S. claims progress, Canada keeps supply management intact. Quota fill rates? They probably stay about the same.

What this means by farm size:

Under 100 cows: Focus on local markets and direct sales. Canadian access won’t materialize in meaningful ways for you anyway. Consider value-added products where you control the whole chain.

100-500 cows: Keep flexibility for quick pivots. Maybe maintain current production, but don’t expand based on export hopes. Watch Southeast Asian opportunities instead.

500+ cows: You’ve got scale to weather this, but don’t count on Canadian markets in your five-year plans. Consider leading industry advocacy efforts—you’ve got the most to gain if something breaks loose.

Scenario 2: Real Enforcement Mechanisms (30% probability)

If those ITC findings are compelling and U.S. negotiators credibly threaten not to renew, Canada might accept automatic penalties for under-utilization or mandatory non-processor allocations. That could deliver partial yet meaningful improvements in access.

Preparation steps if this happens:

- Get your export documentation systems ready now

- Build relationships with potential Canadian buyers

- Understand Canadian labeling and standards requirements

- Consider partnerships with existing exporters to learn the ropes

Scenario 3: A Standoff (25% probability)

Neither side budges much. The agreement goes into annual review mode, creating ongoing uncertainty but avoiding immediate disruption. Both industries operate under this cloud of potential future changes.

Risk management if we hit a standoff:

- Maximum Dairy Margin Coverage enrollment becomes essential

- Lock in feed costs wherever possible

- Diversify buyer relationships domestically

- Don’t make major capital investments based on export assumptions

Who’s Pushing for What: The Players Making Things Happen

Let me tell you about the organizations driving this whole thing, because understanding who’s involved helps make sense of the dynamics.

On the U.S. side, you’ve got some heavy hitters:

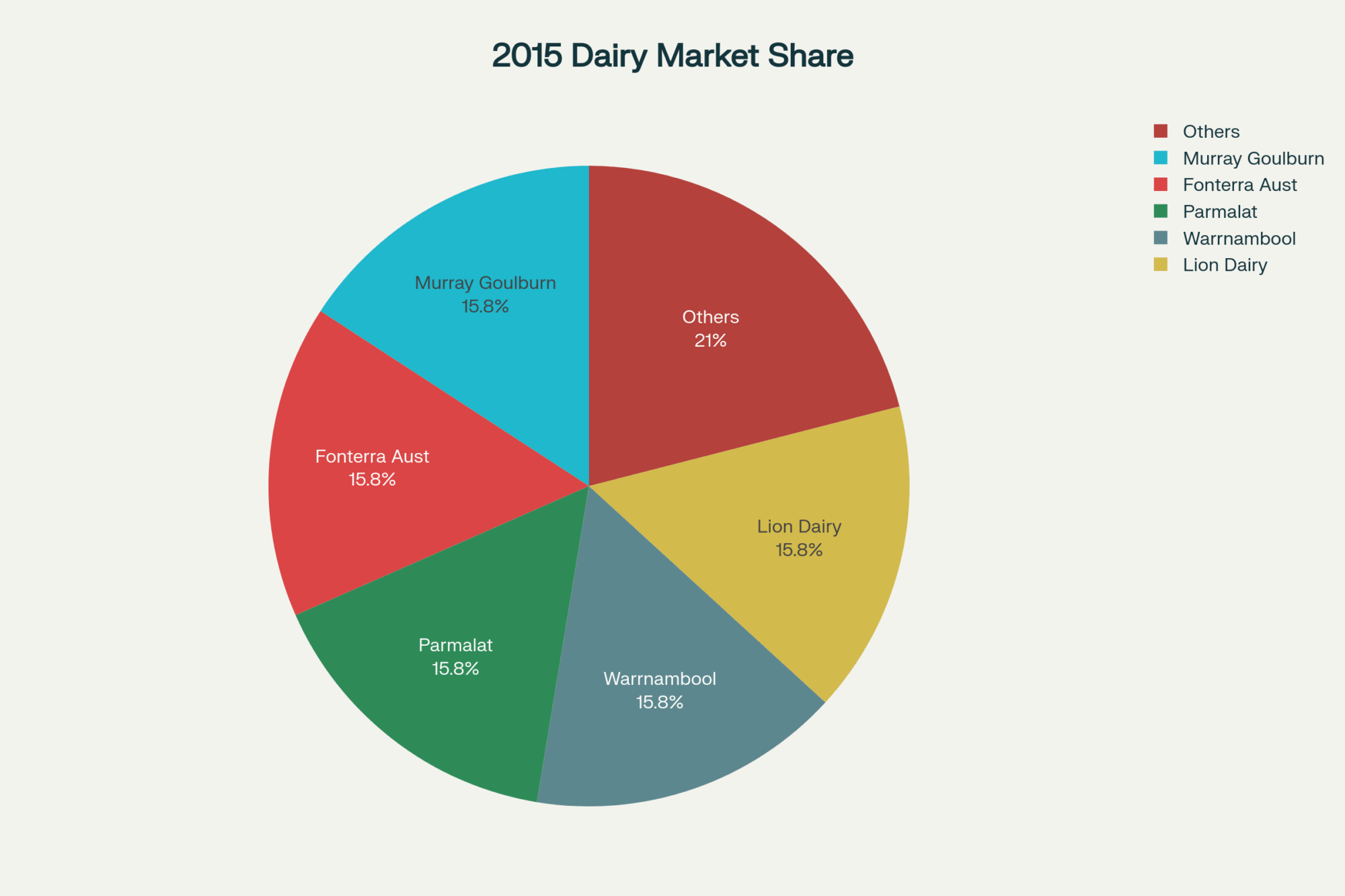

The International Dairy Foods Association—they’re the ones who filed that October 2025 complaint. They represent processors, and they’re pushing hard for what they call an end to protectionist measures. They want binding enforcement, and they want it now.

National Milk Producers Federation lobbied hard for that ITC investigation. They’re your farmer cooperatives, and they keep hammering on automatic penalties for non-compliance. They’ve got members losing money, and they’re not shy about saying so.

The U.S. Dairy Export Council is more technical—they document barriers, provide negotiating support, and help with the nuts and bolts. Edge Dairy Farmer Cooperative represents those Midwest producers, and they’re great at putting farm-level impacts front and center.

On Canada’s side, it’s equally organized:

Dairy Farmers of Canada maintains they’re fully complying with USMCA. They’ve got a consistent message: supply management is legitimate policy, and they’re following the rules.

Les Producteurs de lait du Québec—now these folks have serious clout. They represent Quebec’s 4,877 dairy farms, and in Canadian federal elections, Quebec matters. A lot.

Provincial marketing boards coordinate the defense while implementing those quota allocation systems that the U.S. finds so frustrating.

Market Alternatives: What Some Smart Operators Are Doing

While this U.S.-Canada dispute dominates headlines, some American producers are zigging, while others are zagging. Take this example—a California operation recently told me they doubled their Vietnam exports in 18 months. “The middle class there is exploding,” they said. “They want quality dairy, and there’s no quota games to navigate.”

Industry data from USDEC backs this up—U.S. dairy exports to Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries keep climbing year over year. Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines—they’re importing more dairy each year. No supply management system to work around. Just straightforward business based on quality and price.

You know what’s interesting about these markets? They’re growing fast enough that even mid-size operations can find niches. Specialty cheeses, high-quality milk powders, and even fluid milk in some cases. The logistics are getting better every year, too.

The Bottom Line: No Easy Resolution in Sight

That $850 million figure the U.S. dairy industry keeps citing? That’s their calculation of lost opportunities. Canada disputes both the number and the whole premise. Five years of USMCA implementation have revealed fundamental disagreements about what the agreement actually requires and what compliance entails.

Canada’s supply management system has survived more than 30 years of trade negotiations. Honestly? It’ll probably survive this challenge too. The question isn’t whether USMCA will fully open Canadian dairy markets—nobody really expects that. It’s whether the 2026 review might produce some incremental changes that partially address U.S. concerns while keeping Canada’s core system intact.

The way American producers see it, success means binding enforcement mechanisms with automatic penalties. The way Canada sees it, success is maintaining supply management’s essential structure while offering enough procedural adjustments to avoid a broader trade confrontation.

Come July 2026, we’ll see whether these positions can be reconciled—or whether North American dairy trade stays defined by promises unfulfilled and expectations unmet. Either way, it’s going to be interesting to watch. And whatever happens, we’ll all need to adapt our operations accordingly.

One thing’s for sure—whether you’re milking 50 cows or 5,000, whether you’re in Wisconsin or Quebec, this dispute affects the entire North American dairy landscape. Understanding both sides helps us all prepare for whatever comes next.

Resources for Following This Issue:

Trade Documentation:

- IDFA USMCA analysis: www.idfa.org/usmca2026

- USMCA Secretariat dispute rulings: www.usmca.org

- Statistics Canada dairy trade data: www.statcan.gc.ca

- USDA Foreign Agricultural Service reports: www.fas.usda.gov

Research Centers:

- University of Wisconsin Center for Dairy Profitability: cdp.wisc.edu

- Université Laval CREATE dairy economics: www.create.laval.ca

- Canadian Dairy Information Centre: www.dairyinfo.gc.ca

The Bullvine continues tracking developments from both perspectives as we approach the July 2026 USMCA review. For ongoing analysis, visit www.thebullvine.com.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Both sides have valid arguments: U.S. proves Canada allocates 85% of quotas to processors who won’t import (42% fill rate); Canada’s November 2023 panel win says that’s technically legal

- Real farms, real consequences: 1,420 U.S. operations closed waiting for promised access, while Canadian farmers defend $30,000/cow quota investments—everyone has skin in this game

- July 2026 is unprecedented leverage: The sunset clause means all three countries must actively agree, or $780B in trade enters chaos—first time the U.S. can credibly threaten the whole relationship

- History suggests incremental change: Supply management survived 30+ years of trade fights; expect minor adjustments, not market revolution

- Your operation, your strategy: Under 100 cows = stay local; 100-500 = maintain flexibility; 500+ = lead advocacy while developing Asian markets where actual growth exists

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Your 2025 Dairy Gameplan: Three Critical Areas Separating Profit from Loss – While the main article covers external market risk, this guide provides internal operational control. It reveals specific tactics for optimizing silage, nutrition, and transition cows to improve your cost of production and financial resilience.

- Global Dairy Market in 2025: Production Shifts, Demand Fluctuations, and Trade Dynamics – Go beyond the USMCA dispute. This strategic analysis details how production in Europe and demand in China will impact global milk prices, providing a crucial wider lens for your long-term planning.

- Tech Reality Check: The Farm Technologies That Delivered ROI in 2024 (And Those That Failed) – Before investing to counter market uncertainty, read this. It provides a data-driven breakdown of which technologies, from robots to health sensors, actually delivered a verifiable return on investment for producers last year.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!