Pacific Northwest farmers are finding bold and creative ways to cope with environmental challenges.

Pacific Northwest farmers are finding bold and creative ways to cope with environmental challenges.

Fixing things that had never been a problem before has become a common theme for dairy farmers Michelle and Lonny Schilter. Like others across Washington state, their 500-cow organic dairy especially suffered during record-breaking heat coupled with low rainfall in the summer and fall months.

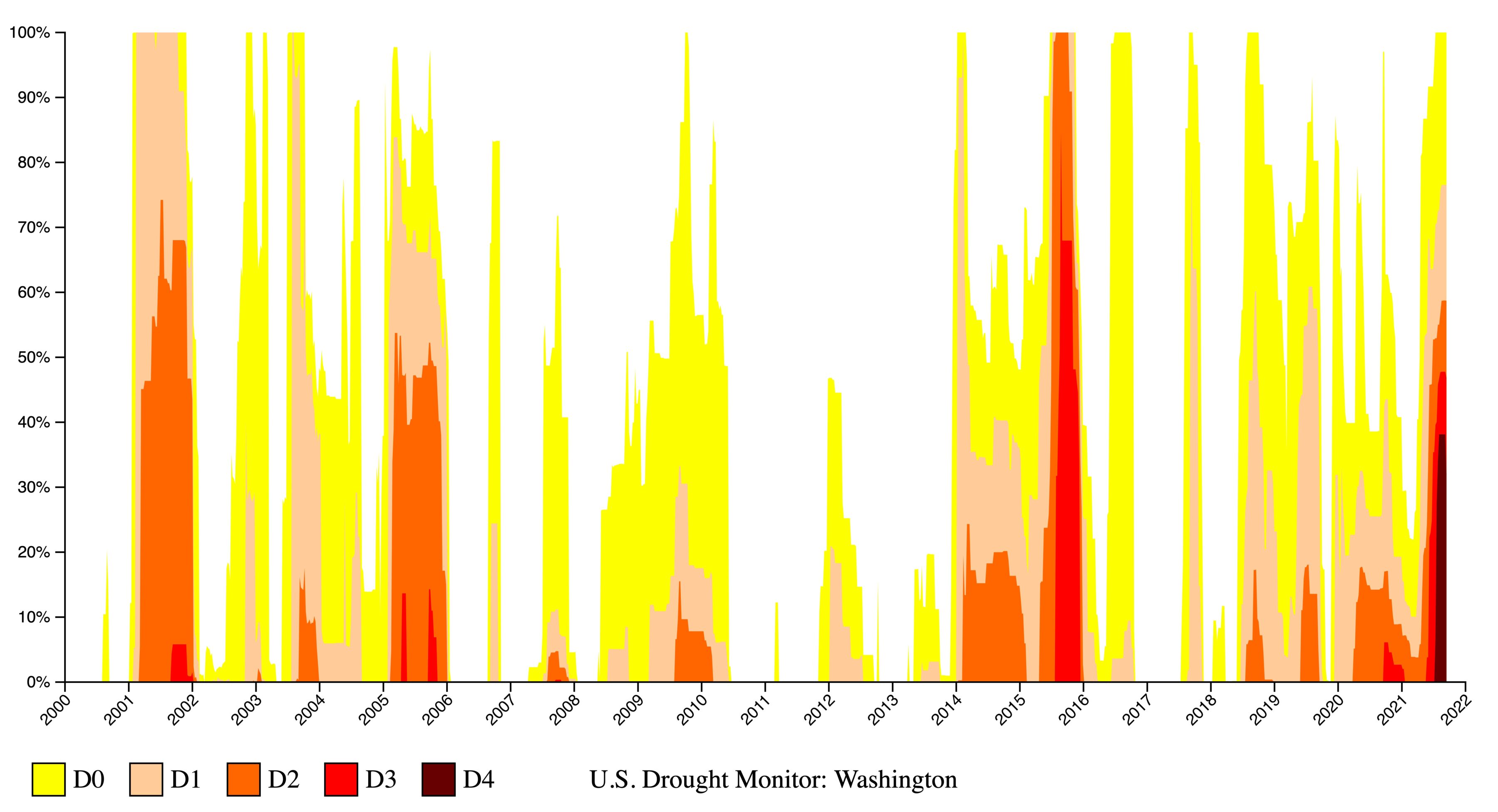

An almost state-wide drought emergency was declared on July 14, 2021 — with more of the same projected in future years.

The University of Washington reports that temperatures in the Pacific Northwest rose about +1.3°F between 1895 and 2011, with “statistically-significant warming occurring in all seasons except for spring.” This trend combined with diminishing snow, ice and streamflow levels will continue to present challenges to farmers like the Schilters.

At the other extreme, last November, thousands of acres of farmland in British Columbia and areas in nearby Washington were inundated with floodwater, putting up to almost 15,000 people under emergency evacuation orders. Officials declared a provincial state of emergency on November 17, 2021.

Faced with the loss of animals and damage to land, homes, outbuildings and on-farm technology, how are farmers coping?

Dairy farm near Sumas, Washington. Photo courtesy Unsplash.

Lack of water

In September, when The Daily Churn spoke with Michelle, it had been three months since the farm received any significant rain. With both lagoons empty, the family had limited ways to irrigate the fields and their grass stopped growing.

“Until about six or seven years ago,” Michelle said, “we never had a problem meeting our organic certification requirements. The cows were out on pasture all summer, so it was easy to reach the 120-day minimum.”

This year, there has been so little water in the dedicated dairy well that it became difficult to flush clean the barns each day. Lonny frequently switches the direction of their piping in order to use the home well to provide water for the dairy.

“It’s gotten to the point where all we can do is wait,” said Michelle. “We’re assuming that this state of emergency is going to occur more frequently, so we’re considering different management options.”

She added that they have a couple of fields that border the Chehalis River. “We’re looking into the possibility of gaining access to that water for those specific fields.”

Chart showing drought in Washington State, USA, from 2000 to the present. The most intense period of drought occurred the week of August 3, 2021, where D4 affected 38.13% of Washington land. Data from the US Drought Monitor

The dairy community rallies to help

After a month’s worth of rain fell in two days, farmers on the rich land of the Sumas Prairie in Abbotsford, British Columbia faced the heartbreaking necessity of leaving behind the animals they didn’t have time to evacuate. At its peak, the flooding put 62 farms under evacuation orders.

At one point, all major roads between the country’s Interior and BC’s Lower Mainland were inaccessible, preventing feed supplies from arriving and farmers and their animals from leaving.

Holder Schwichtenberg, dairy farmer and chair of the BC Dairy Association Board, told The Daily Churn that the question farmers were asking swiftly changed from “Can you take some cows?” to “How many can you take?”

“The water rose so fast,” he added, “that most cows stayed in their barns.”

Still, Schwichtenberg said the dairy community rallied to take care of their neighbors. “The spirit of giving was phenomenal,” he said. “We had trucks and trailers of all sizes helping haul five or six thousand cattle out of the area.”

Farmers in safer areas took in as many animals as they could, milking and feeding them along with their own.

With such incidents of extreme weather growing more frequent throughout the year, some farmers are looking ahead.

The only certainty is change

Michelle told The Daily Churn they are planning ahead to ensure continued resilience in the face of uncertainties.

“Making the right decisions now is crucial to our farm’s survival,” she says.

Among other things, some years ago, they installed a second lagoon and new wells, which Michelle says have helped them “beyond measure.”

“But of course,” she adds, “we couldn’t have known at the time how essential those changes would be to us at this point.”

When Lonny’s father built the free stall dairy, he received a lot of pressure to go with a more traditional, enclosed barn design. Yet it has been the barn’s ability to catch any breeze and move it across the cows that has allowed the herd to stay cool naturally, eliminating the need for extra expenditure on fans and misters.

Around 20 years ago, the Schilters decided to put in a second lagoon in order to capture as much of the winter rain and snow as possible. Located where they are in western Washington, they knew that having additional water available in the summer would at some point become a critical management tool.

“That’s been a lifesaver for us,” Michelle says. “I remember when we didn’t have it. I don’t know what the farm would look like without it.”

Similarly, when the well that supplies the house went bad and had to be replaced shortly after Michelle and Lonny moved in, the couple decided to expand the replacement project. They added piping and an additional well to serve the dairy.

It was a classic case of saving time and money in the future by expending a bit more at the start.

Forest image published on Unsplash November 14, 2018.

More recently, the family decided to log the forested part of their property and use the proceeds to install milking robots.

They are going to plant new trees with the hope that in 40 years, the new forest will provide a pension for their children. They hope the robots will help reduce the financial pressures that have resulted from increasingly common climate extremes.

Unfortunately, volatile weather creates other challenges for farmers.

Repairing health

“We were on half rations for nine days,” Schwichtenberg says of the flooding’s affect on feed for livestock.

In addition to his own herd, he was feeding and housing 13 lactating and nine dry cows owned by other farmers. He says that lack of nutrition combined with physical and mental stress is likely to affect thousands of cows’ production rates for unknown periods of time.

Crops not yet harvested were ruined by the flooding, and many stores of feed and other supplies were under water for hours or days, making them unusable. Freezing winter weather further complicated the work the farmers faced in rebuilding barns and repairing electrical systems and other equipment.

Several big name brands including Gay Lea Foods, Vitalus Nutrition and Agrifoods Cooperative donated money and supplies to farmers, while groups like BC Dairy are continuing to help farmers recover.

The stress of farming is a recognized health risk, with organizations ranging from the American Psychological Association (APA), the Rural Health Information Hub and the University of New Hampshire (UNH) publicising a range of resources designed explicitly for farmers.

An August 2021 Facebook post by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture advertising mental health services received almost 2,500 clicks in the first two weeks of it being online. Meanwhile, Washington State’s interim state veterinarian told the New York Times that farmers need to remember to take care of themselves, too.

“I’m one of the lucky ones,” Schwichtenberg said. “I cannot imagine what it would be like to drive away from your farm and leave it under water, leaving your animals behind. It’s absolutely heartbreaking!”

Source: darigold.com

Pacific Northwest farmers are finding bold and creative ways to cope with environmental challenges.

Pacific Northwest farmers are finding bold and creative ways to cope with environmental challenges.