Foreign investment in U.S. agricultural land is a hot topic, largely spurred by media reports raising concerns about bad actors from adversarial nations purchasing land for potentially hostile purposes. Several questions arise when considering this issue. First and foremost, how much agricultural land in the U.S. is owned by foreign investors and from what countries do those investors hail? Second, what kind of land do these foreign entities own? Productive cropland? Forestland? Or perhaps open space for energy production or other purposes? Additionally, how have these numbers changed in recent years? While data exists to answer many of these questions, the quality of these data points has often been questioned, complicating our true understanding of how much U.S. ag land is owned by foreign investors and who they are. This article summarizes the latest available data with some critiques of its quality.

As noted in a January Congressional Research Service report, the Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act of 1978 (AFIDA) established a nationwide system for collecting information pertaining to foreign ownership of U.S. ag land (defined as land used for forestry production, farming, ranching or timber production). AFIDA defines a foreign person to include “any individual, corporation, company, association, partnership, society, joint stock company, trust, estate, or any other legal entity” (including “any foreign government”) under the laws of a foreign government or with a principal place of business outside the United States. U.S. citizens and green card holders are explicitly excluded from AFIDA requirements. The regulations require foreign persons who buy, sell or gain interest in U.S. agricultural land to disclose their holdings and transactions to USDA directly or to the Farm Service Agency office where the land is located. Failure to disclose this information may result in penalties and fines through USDA investigative action. Maximum civil penalties of up to 25% of the fair market value of the interest held in land can be levied for those who fail to comply. The accuracy of disclosed data relies on voluntary compliance and self-reporting by the foreign entities.

Summary of USDA AFIDA Data

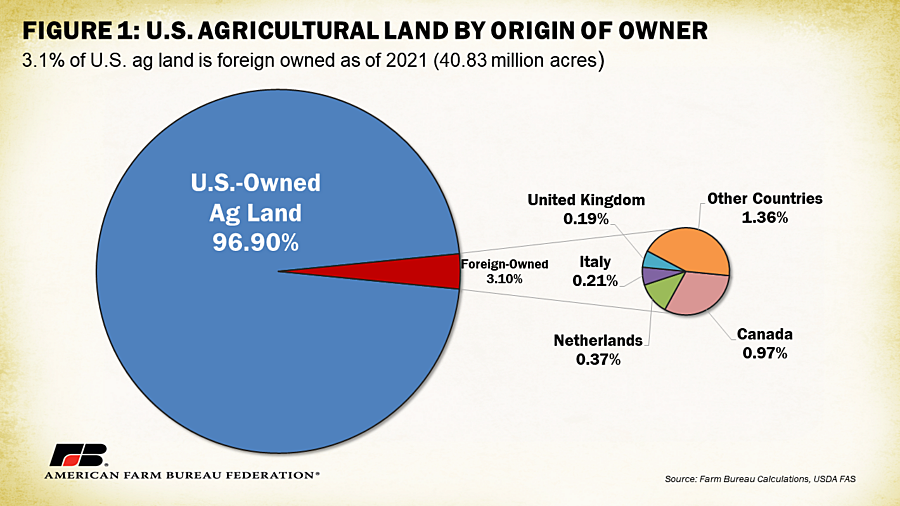

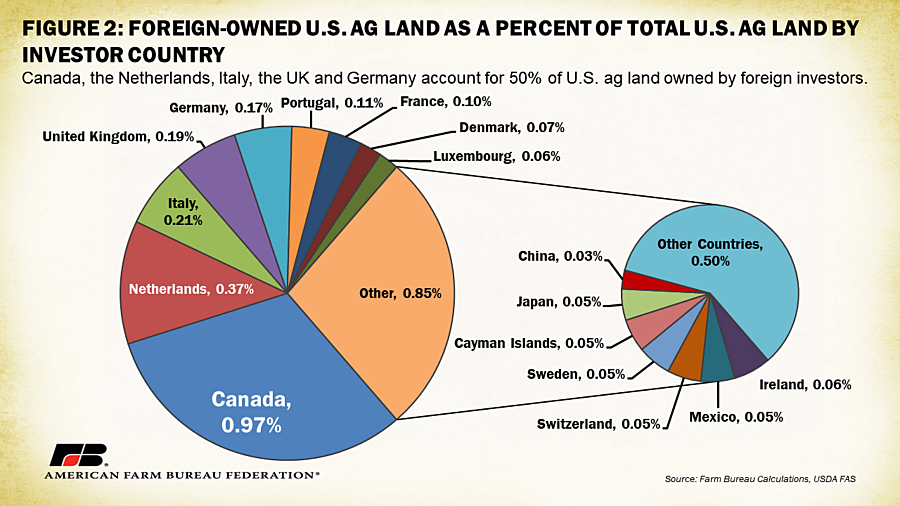

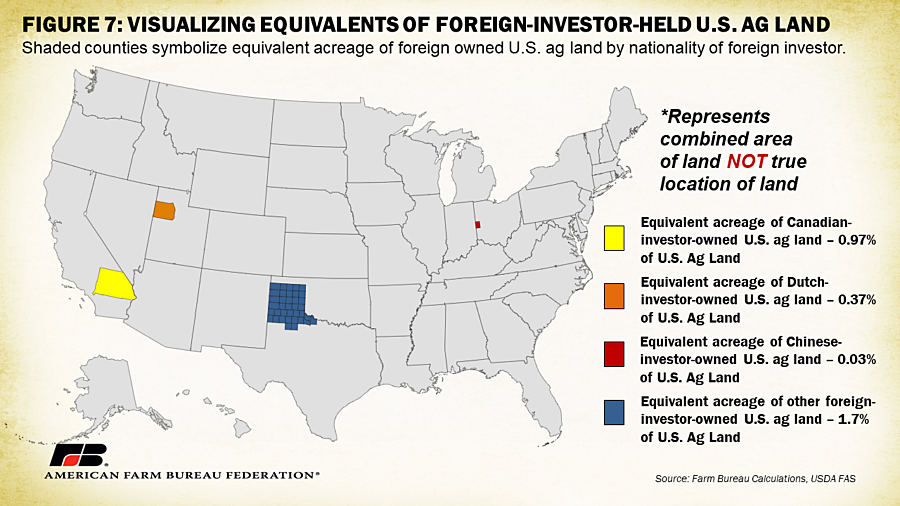

According to USDA’s latest AFIDA report, which is based on 2021 data, over 40 million acres of U.S. agricultural land are owned by foreign investors and companies. This corresponds to 3.1% of all privately held agricultural land and 1.8% of all land in the United States. Canadian investors own the largest portion of foreign-held U.S. agricultural land with 31% (12.8 million acres) of the total and 0.97% of all U.S. agricultural land. Following Canada, investors from the Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom and Germany own 0.37% (4.9 million acres), 0.21% (2.7 million acres), 0.19% (2.5 million acres) and 0.17% (2.3 million acres) of U.S. agricultural land, respectively. Over 52% of the reported acreage was listed under the category that includes limited liability companies (LLCs), 32% was corporations (most of which were formed in the United States), 12% was partnerships, 2.3% was individuals and the remainder was split between trusts, estates, institutions and associations. Figure 2 further breaks down foreign-investor-held land by predominant origin nation.

County, State and Land Use Data

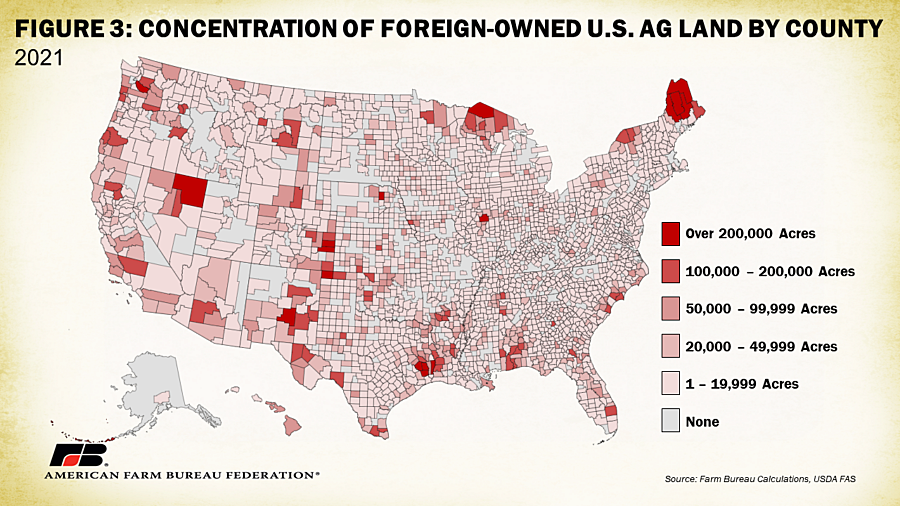

Figure 3 displays the concentration of reported foreign-investor-held agricultural land by county. Of the 3,142 counties and parishes in the U.S., 2,494, or 79%, have at least one foreign investor present. In 2,041 counties, or 65% of counties, foreign investors own between 1 and 19,999 acres of land. Only 18 counties, or 0.01% of all counties, have over 200,000 acres of agricultural land held by foreign investors, the top four of which are in northern Maine with Canada-based investors. A little over 20% of Maine’s privately held agricultural land is held by foreign investors, which makes up 9% of total foreign-held ag land. Hawaii has the second-largest percentage of foreign-held U.S. agricultural land, which is 9.2% of the privately held agricultural land in the state.

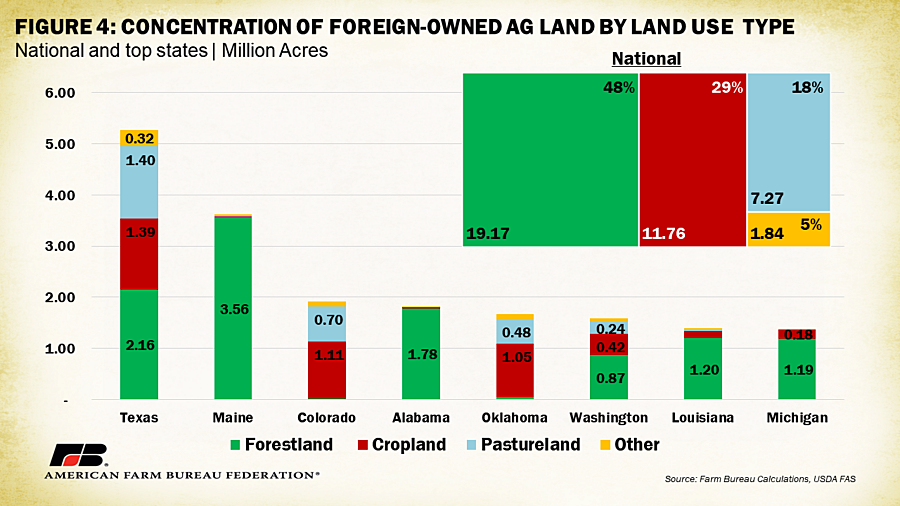

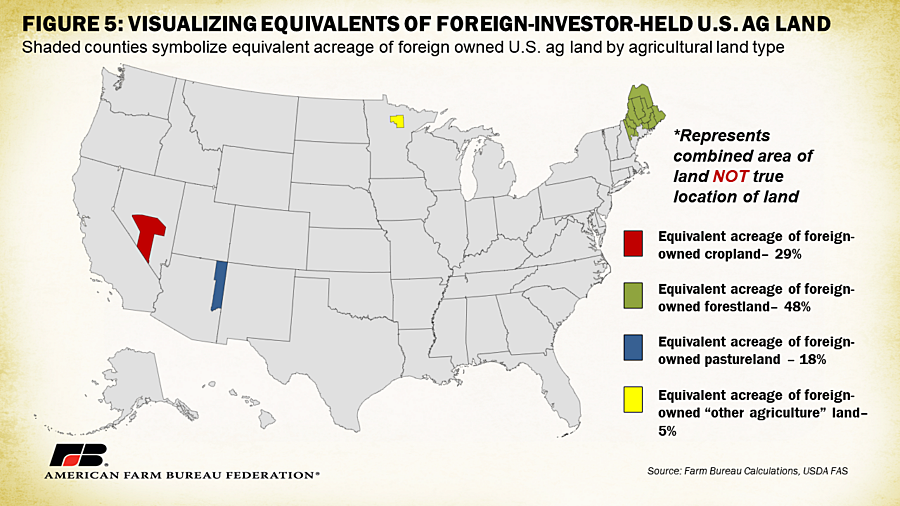

In 2021, 48% (19.2 million acres) of reported foreign-held agricultural land was forestland, 29% (11.8 million acres) was cropland, 18% (7.3 million acres) was pastureland and 5% (1.8 million acres) was other agricultural land and non-ag land, which accounts for factors like owner or worker housing and rural roads. These proportions vary widely depending on the state. Forestland, for instance, makes up 99%, 98%, 86% and 85% of foreign-held agricultural land in Maine, Alabama, Louisiana and Michigan, respectively. In states with significant timber industries, this land is primarily held by investors from Canada and the Netherlands. Of the top eight states with the highest concentrations of foreign-investor-held land, only two (Colorado and Oklahoma) have cropland as their largest foreign-held land category, with investors primarily from Canada, Italy and Germany.

Visualizing the area of foreign-investor-held acreage can be difficult in standard county-level heat distribution maps. Figure 5 displays county equivalents of foreign-investor-held agricultural land by category if all separately owned parcels of land were combined and placed in the same geographic location. Counties shaded green reflect the total acreage equivalent of foreign-investor-held forestland combined from across the country. Counties shaded red reflect the comparable total acreage of foreign-investor-held cropland combined from across the country. Counties in blue and yellow reflect the total acreage equivalent of foreign-investor-held pastureland and other agricultural land combined from across the country, respectively. Combined, this acreage reflects an area 3 million acres shy of the combined acreage of Ohio and West Virginia, most of which is forestland.

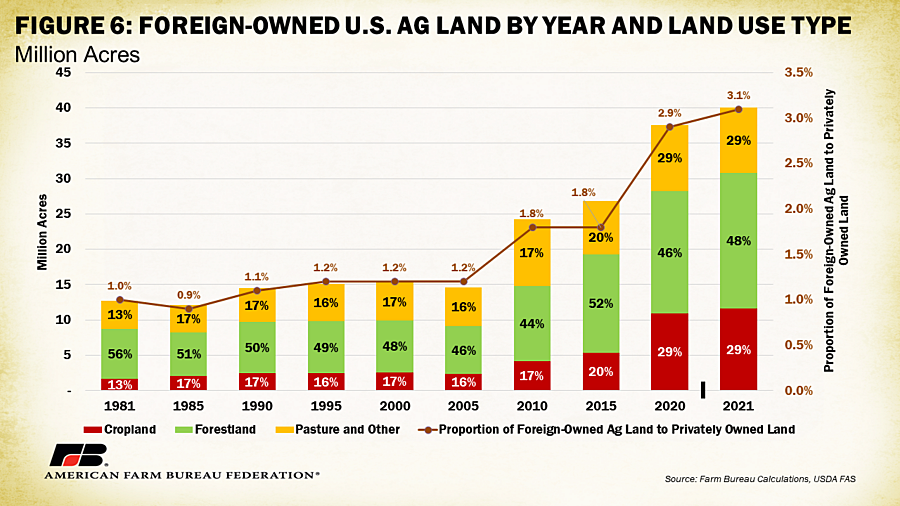

Analyzing the quantity of reported foreign-investor-held U.S. agricultural land overtime reveals a 27-million-acre increase (214%) in the four decades since AFIDA reports were made available. This reflects an increase from 1% of total privately held agricultural land in the U.S. to 3.1%. Between 2010 and 2021, foreign-investor-held agricultural land increased 15.8 million acres, with cropland increasing at the highest percent (182%) with an additional 7.5 million acres, forestland increasing the highest numerically at 8.6 million acres (80%) and other ag land declining 3% or 240,000 acres.

As noted in the latest AFIDA report, states showing the highest increases in foreign-investor-held agricultural acres between 2020 and 2021 were Texas, with an increase of nearly 549,000 acres; Arkansas with an increase of nearly 250,000 acres; and North Carolina, with an increase of nearly 247,000 acres. Forty-three percent of the overall increase in acreage between 2020 and 2021 is attributed to these three states. Hawaii, Iowa and Utah are the only states showing a decrease in foreign-held agricultural acres; the over 52,000-acre decline reflects long-term leaseholds that were terminated and the sale of various types of agricultural land.

The top 10 entities reporting foreign-investor-held agricultural land, in terms of acreage, hold 7.22 million acres of U.S. agricultural land, which corresponds to 0.6% of all U.S. agricultural land and 18% of foreign-held agricultural land. Only a limited few involve land used in crop production and the vast majority correspond to nations considered very friendly to U.S. interests. Seven of these top 10 entities are timber or timber-adjacent industry participants. This includes two Canada-based timber companies which own 1.11 million acres and 963,600 acres in northern Maine, respectively; a Netherlands-based timber company which holds over 748,000 acres across South Carolina, Arkansas and Louisiana; an Ireland-based corrugated packaging company that holds 617,000 acres across Florida, Alabama and Georgia; a third Canada-based timber company which holds 352,000 acres in Texas; a Sweden-based timber company which holds 300,000 acres in Texas; and a fourth Canada-based timber company which holds an additional 297,000 acres in Maine. The largest single landowning foreign entity is a multinational power generation development company that holds 1.709 million acres of land across 25 states (the largest concentration of which – 473,000 acres – is in Colorado). Though the energy company is a U.S.-based entity, in 2013 Quebec’s public pension fund manager invested heavily in the company’s portfolio of wind farms, making Canada the prominent investor for the nearly 2 million acres of corresponding wind energy generation land. Similarly, a wind energy company holds 391,000 acres across Oklahoma for a proposed renewable energy generation facility. The company is based in the panhandle of Oklahoma, with significant Canadian investments for the reported acreage. The only entity not explicitly related to timber or energy production in the top 10 is an insurance company, which manages a wide portfolio of assets including 1.296 million acres of agricultural land across 18 states. (The largest concentration of which – 180,000 acres – is in Oregon.) The New England-based company was acquired by a Canadian life insurer in 2004. The bulk of AFIDA reports mimic the distribution of these top 10 land-holding entities with major land holdings primarily by energy production and timberland investors. Company names and the list of corresponding counties they own agricultural land in can be found here.

The National Security Factor

Many of the current concerns about foreign ownership of U.S. ag land have focused on China. According to the latest AFIDA data, China is ranked 18th in the ownership of U.S. ag land with 383,000 acres, less than 1% of total foreign-owned U.S. ag land, or just three hundredths of one percent of all agricultural land in the U.S. This reflects a total area about one third of the size of Rhode Island or that of an average sized county in Ohio. Figure 7 allows us to visualize this more clearly. Shaded counties reflect county equivalents of foreign-investor-held agricultural land by nationality of investor or company if all separately owned parcels of land were combined and placed in the same geographic location. Counties shaded yellow reflect comparable total acreage of Canadian-investor-held ag land combined from across the country. Counties shaded orange reflect the geographic equivalent of the total acreage of Dutch-investor-held ag land combined from across the country. Counties shaded blue reflect the comparable total acreage of all other foreign-investor-held ag land combined from across the country and the county shaded red reflects the total equivalent acreage of Chinese-investor-held ag land combined from across the country. Combined, Canadian-investor-owned acreage is 2.5 million acres shy of the size of West Virginia, while Dutch investors own acreage about 600,000 acres shy of the size of New Jersey and investors from other nations own acreage about the size of the Texas panhandle.

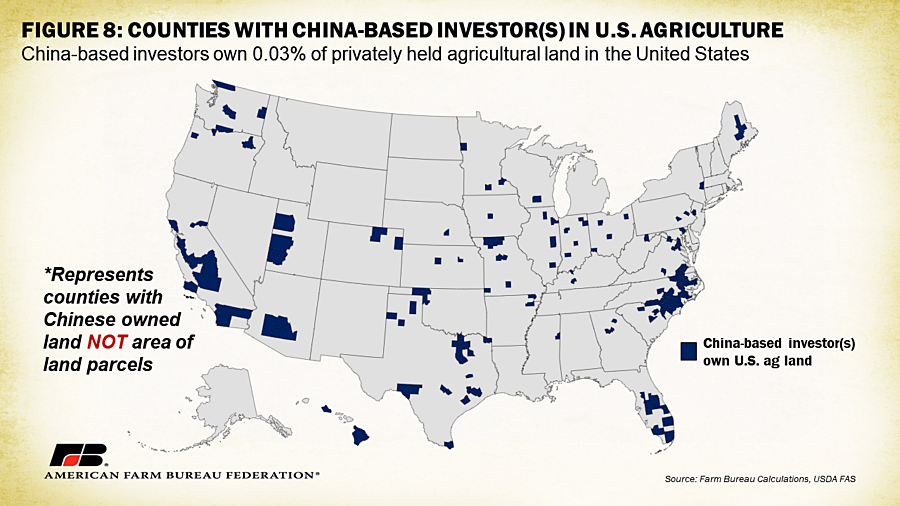

Figure 8 displays counties where Chinese investors and companies have a stake in U.S. agricultural land. By acreage, about 192,000 acres (50%) of Chinese-investor-held U.S. agriucltural land are located in Texas, 49,000 acres (13%) are located in North Carolina, 43,000 acres (11%) are located in Missouri, 34,000 acres (9%) are located in Utah and the remaining 17%, or 66,000 acres, is scattered across 24 other states.

According to AFIDA data, about 131,000 acres located in Texas represent the largest single parcel owned by a Chinese-based billionaire investor. Previous news coverage states the individual purchased the land for a wind farm, with an additional 30,000-acre parcel in the same county. The cited article reports that the project was ultimately halted by a state law designed to stop foreigners from accessing the Texas electricity grid. Second to these Chinese-owned Texas properties, which make up over 40% of Chinese-investor-owned U.S. ag land, are the properties of a Virginia-based U.S. pork processing company that was was acquired by a Chinese-owned firm in 2013. These properties account for over 146,000 acres of U.S. agricultural land spread across nine different states. Nearly 49,000 acres owned by this pork processor are located in North Carolina, 33,500 acres are located in Utah and 13,300 acres are located in Virginia. Third, a land asset management and global real estate investment company headquartered in Scottsdale, Arizona, and includes Chinese investors, owns over 30,000 acres spread across seven states but primarily in Texas (16,300 acres) and Arizona (9,500 acres). Additionally, a global seed and pesticide company acquired by a Chinese-owned firm in 2017 holds close to 6,000 acres of land across 16 states primarily used to conduct research to develop and deliver seed and crop protection products for farmers around the globe.

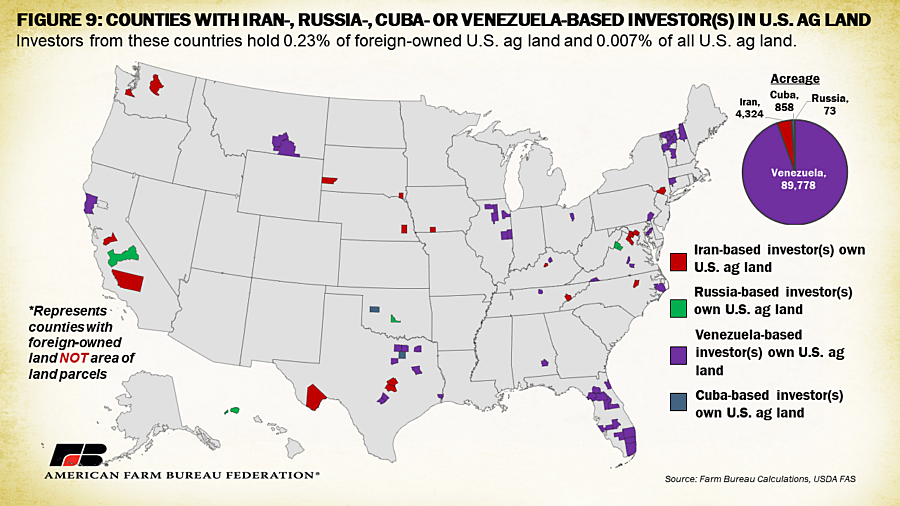

The list of current adversarial nations as defined by the Department of State also includes the Republic of Cuba, Islamic Republic of Iran, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea), the Russian Federation and Venezuela under the Maduro Regime. Combined, investors from these additional nations hold about 95,000 acres of agricultural land in the United States, which corresponds to 0.007%. Venezuelan investors make up nearly 95% of this total with about 90,000 acres across 17 states. Florida holds the largest area of Venezuelan-investor-owned land with 43,500 acres, not surprising considering the history of Latin American influence in the region. One sugar company is the largest of these Florida-based Venezuelan parcels with over 14,000 acres. A land holding company owns nearly 21,000 acres in southern Montana – the largest Venezuelan-investor-owned parcel in the nation. Iran-based investors follow Venezuela distantly with 4,324 acres of U.S. agricultural land across 13 states. Additionally, Cuba-based investors hold 858 acres in three states and Puerto Rico, Russia-based investors hold 73 acres in four states and no land was reported under North Korea.

Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States

Historically, the U.S. has reviewed national security concerns with foreign investments in U.S. companies and assets via the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). Investigations into mergers and acquisitions that could result in foreign control of a U.S. business, targeted investments into critical technologies, infrastructure, or personal data and real estate transactions have fallen under the jurisdiction of CFIUS. CFIUS investigated, and approved, the Chinese-firm acquisitions of the pork processor and seed company mentioned above. An interagency committee, CFIUS is chaired by the secretary of the Treasury with eight other members including the secretaries of State, Homeland Security, Commerce and Energy; attorney general, U.S. trade representative; and director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy. Additionally, the secretary of Labor and director of National Intelligence hold positions as ex-officio members. Five White House offices are observers in CFIUS, often including the National Security Council. The president can appoint other officials to serve on a case-by-case basis. Notably, the secretary of Agriculture has not played an active role in CFIUS, a possible oversight given the link between domestically secure agricultural production and national security and the growing focus on foreign purchases in ag land.

Data Limitations

Notably, one clear challenge of existing AFIDA data is the lack of enforcement. Between 1998 and 2021 USDA penalties were assessed 494 times on 395 different investors, though all fees assessed were for late filing rather than avoiding filing. All penalties have been less than 1% of the market value of interest held in the land compared to the maximum penalty of 25%. And no penalties were assessed between 2015-2018 and 2020 due to staffing shortages at USDA.

Ownership transparency is also limited because USDA lacks the authority to require disclosure beyond a third tier of ownership, which means they cannot always identify the “identity of the ultimate beneficial owner” or their corresponding true location. The lack of resources at USDA to enforce AFIDA has resulted in practical limits to policing the high volume of annual real estate transactions, with nearly half of all transactions not disclosing a price. There are over 3.2 million acres, or 8%, of foreign-investor-held agricultural land that is uncategorized, either because the submission had “no foreign investor listed” or “no predominant country code listed.” It is also important to note USDA assigns a country based on the investor with the largest share, even if that share is minimal and not a controlling interest. Overall, the presented numbers need to be viewed with these data limitations and concerns in mind and demonstrate that improvements should be made in the AFIDA data.

Policy Considerations

Regardless of the interpretation of the above statistics, actions at both the state and federal level have signaled a desire by some to either restrict foreign ownership of U.S. agricultural land or improve data collection and disclosure enforcement. The National Agricultural Law Center has compiled a list of state-by-state statutes regulating ownership of agricultural land, which can be accessed here. A July 2023 Congressional Research Service report also provides a good overview of these laws as well as current congressional considerations. Strong arguments for and against further restricting ag land purchases have been made. Concerns about the federal government having a larger role in restricting the freedom of individuals to sell private property have often been expressed. Others have targeted restrictions to only adversarial nations, though nuances in how adversaries should be defined or how to react when a country should be added or removed have complicated discussions. Only restricting land purchases near sensitive military sites or vital energy infrastructure has also been considered. In addition, there are worries that excess regulation could hinder the flexibility of farm transitions. Family operators whose children do not want to continue working on the farm have reported wanting to pass the land onto immigrant workers who have shown an interest in managing operations. In these situations, or others that concern immigrants having an interest in farming, regulations that concern an individual’s nationality and citizenship could be a hurdle to the farm’s future. Furthermore, several farm groups and lawmakers are calling for the United States Secretary of Agriculture to be a permanent member of CFIUS.

Conclusion

The data made available from AFIDA reports provide a limited yet detailed window into foreign-investor-held agricultural land dynamics in the United States. Reported foreign-investor-held agricultural land as a percent of total U.S. agricultural land remains small but has increased from 1% to 3.1% since AFIDA’s inception. The vast majority of this land is owned by investors from nations considered friendly to the U.S., though data reporting limitations prevent us from accessing a precise breakdown. Additionally, forestry and energy production are the main interests for these parcels. Adversarial nations’ investments remain a very small portion of foreign-investor-held agricultural land, though, again, data and reporting challenges prevent our complete knowledge of these dynamics. Improvements to collection and enforcement would appear to be a meaningful way for consumers, farmers and policymakers alike to better understand this issue. Furthermore, understanding the sensitivities of each individual investor situation, their history, and the implications for agriculture regionally are all likely to be considerations for legislative or policy actions.

Source: FB