Many of the Kentucky dairy farmers who sold their milk to Dean Foods have not yet found anyone else to buy it instead — and like Coombs, they could soon have to sell their cows. They are just the latest of more than 42,000 dairy farmers who have gone out of business since 2000, casualties of an outdated business model, pricey farm loans and pressures from corporate agriculture.

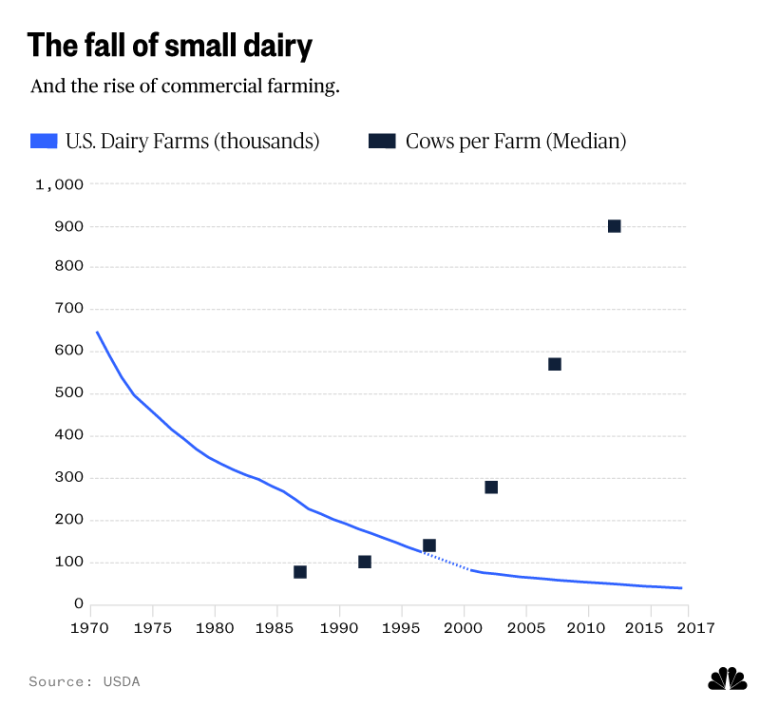

There were nearly 650,000 dairy farms in the U.S. in 1970, but just 40,219 remained at the end of 2017, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Cows are producing more milk than ever, but they’re consolidated on bigger, more efficient farms. In 1987, half of American dairy farms had 80 or fewer cows; by 2012, that figure had risen to 900 cows.

Small dairy farmers, an aging population, were some of the last U.S. holdouts against the farming industry’s pressure to grow or die — but it’s unclear how much longer they can last. Hope grew when President Donald Trump tweeted support for the dairy industry in early June at the G-7 meeting in Canada, but experts and farmers say Trump mistakenly focused his ire on trade and tariffs rather than an American industry that is increasingly hostile to small-time operators.

Joe Schroeder takes calls from dozens of struggling farmers each month at Farm Aid, an organization founded by musician Willie Nelson to keep family farmers on their land. Small dairy farmers make up a third to half of those calls, Schroeder said. The farmers, who often do the milking themselves or with family members and work 12 to 16 hours a day, tell him about the electricity being turned off and not having money for groceries. They ask advice on declaring Chapter 12 — bankruptcy designed for farmers.

“I don’t see anything that would give them hope at this point,” Schroeder said. “The best advice I can give to these folks, dairy farmers, is to sell out as fast as you can.”

The milk industry in crisis

At Walmart, shoppers in Kentucky can buy a gallon of milk for as little as 78 cents, but that’s far less than what the company paid for it or even what it cost the farmer to produce. Stores often sell milk at a loss since it’s a staple and customers may pick up more profitable items as well.

On average, farmers spend $1.92 to produce a gallon of milk and make $1.32 when they sell it to processors. This is the fourth year in a row that farmers’ milk prices have dipped below the cost of production.

“We could buy all the gallons of milk out of the grocery store, bring them home to our bulk tank, pour it in there and sell it back to them and make more money,” said Carilynn Coombs, Curtis’s wife.

Low milk prices set off a cycle in which farmers produce more milk to ensure they’re bringing in enough money to operate, leading to dairy products flooding the market and prices plummeting still further. Even when the price of milk rises, however, the cycle doesn’t end — farmers keep milking as much as they can to cash in before the price drops again. It’s a never-ending catch-22 of competition that is running dairy farmers aground.

Walmart’s decision to build its own milk processing plant highlights another issue for farmers. In a trend that extends back to the 1970s but ramped up over the past decade, corporate agriculture is increasingly taking control of all stages of milk production, which can leave small farmers with fewer places to sell their milk, said Maury Cox, executive director of the Kentucky Dairy Development Council, an advocacy group. Corporations opening milk processing plants would rather work with fewer large dairy farms than thousands of small ones, Cox added.

“What do you do in this situation when you don’t have a market for your milk?”

That, Cox said, leaves farmers asking: “What do you do in this situation when you don’t have a market for your milk?”

The question is of particular relevance to dairy farmers in the Southeast, where the industry is steeped in a certain regional irony.

While there is a surplus of milk nationwide, Kentucky and the Southeast face a net deficit of 41 billion pounds of milk annually, according to Mark Stephenson, a University of Wisconsin dairy economist. That means that even as dairy farmers in these states struggle, grocery stores there are importing milk in refrigerated trucks from the Midwest.

Why are Kentucky milk farmers being frozen out of the local market? Part of the answer lies with powerful dairy cooperatives, groups of farmers who work together to sell their milk. Dairy Farmers of America, the nation’s largest dairy cooperative, has an incentive to maintain the milk deficit in the Southeast because it gives the group’s members in the Midwest a market.

Fourteen Kentucky farmers recently tried to join the cooperative, but they were denied because the group saw them as competition, the farmers told NBC News.

John Wilson, the group’s senior vice president and chief fluid marketing officer, said that the co-op recognized “the dairy farmers in Kentucky who have been displaced face a tough situation,” but did not provide a clear reason for denying their membership.

“Membership decisions are handled on a regional basis and evaluated based on a number of factors,” Wilson said, “including farms in the area, milk volumes, supply-and-demand conditions and milk quality.”

How Canada milks differently

The struggles of American dairy farmers haven’t extended to their peers north of the border. Canada’s government runs a supply management system that controls the nation’s dairy, egg and poultry output. Canada uses the system to enforce domestic production quotas as well as limit its dairy imports and exports, which keeps prices steady and guarantees farmers a stable income — though it has a larger impact on consumers’ wallets.

Canadian dairy farmers, however, have enough extra money to fix buildings, buy new equipment and even take vacations, said John Kalmey, 66, a small-dairy farmer in Shelbyville, Kentucky, who is on the brink of ending his family’s 80 years in the dairy business and who has spoken to and visited farmers in Canada.

Small-dairy farmers in the U.S. like Kalmey, who average a salary of just over $20,000 a year if they can afford to give themselves one at all, marvel at those luxuries.

“I think it’s a shame we don’t have that same [system] here,” Kalmey said.

The disparity has also caught the attention of Trump, who placed blame for the floundering American dairy industry at Canada’s feet during the G-7 conference in Quebec. Trump attacked Prime Minister Justin Trudeau — calling him “dishonest & weak” — for Canada’s dairy tariff that keeps its farmers afloat. “Our Tariffs are in response to his of 270% on dairy!” Trump tweeted.

Kalmey and other dairy farmers, though, do not believe that an end to the dairy tariffs would be a solution. If anything, removing Canada’s protections would leave dairy farmers there in the same boat as those in the U.S. Some farmers worried that Trump is more likely to cause a trade war than open a new market for them — they fear losing the limited export market that the U.S. currently has, which could cause the price of milk to drop further.

And trade isn’t the main source of the industry’s difficulties: Dairy exports were up 2 percent between 2016 and 2017, according to the USDA. For 2018, the USDA forecasts 7 percent growth.

Loss of historic farms causes economic ripples

Gary Rock, 59, lives in Hodgenville, Kentucky, an area of rolling hills and loose rock fences, on a farm that has been passed down through his family for 300 years. After Dean Foods dropped his contract amid Walmart’s expansion, he expects that he will be the last generation to ever milk a cow on this land.

The past few years haven’t been easy. In 2012, Rock rebuilt his farm after it was hit by a tornado that destroyed all the buildings except the one where he milks his cows. The following year, he lost his legs in a tractor accident, but he kept farming. Then his only employee left after the Dean Foods announcement, so Rock began milking the cows by himself. Now, he must consider selling off portions of his farm to stay afloat.

“That is not what America is about, I’ll tell you that right now,” Rock said.

Source: nbcnews.com