Executive summary

We have seen cow numbers grow from 3.4 million in 2000 to 4.9 million in 2019 and the area being farmed for dairy has increased by 33% over this period.

Underpinning this growth has been continued intensification which has created significant opportunities and prosperity for those in the industry, however like any fast-paced intensification it has created negative impacts on our environment.

As a result, the NZ dairy industry has been challenged to be more environmentally and socially sustainable to ensure we are both proud and responsible within our farming practices. We are beginning to see change in a number of areas across the dairy industry with significant emphasis being placed on climate change, water quality, work conditions and animal welfare.

Despite some initial farmer objections, these developments are all beneficial to the NZ dairy industry, and will enhance our reputation as a world leader in quality produced dairy products.

An area that remains out of the spotlight is on-farm waste and what we are doing to be environmentally responsive. It was the objective of this report to discover current waste and recycling volumes within the NZ dairy sector as well as what is being done about improving waste disposal. The report also sought to determine what is being developed for greater future farmer engagement as well as what is currently being achieved with the recycling we are collecting from dairy farms.

At the commencement of the project the assumption was made that farmers continue to burn and/or bury their waste and that there is a lack of work being completed to address the increasing issue of on-farm waste on dairy farms.

This report has been able to determine that previous work has been undertaken around waste levels and current disposal across the rural sector in New Zealand, and that despite some improvements in disposal practices this is an ever increasing issue that requires immediate attention.

This report identifies several significant studies and the arrival of two key recycling providers into the industry, AgRecovery and Plasback, who have ensured the volumes of recycling collected from New Zealand dairy farmers has significantly increased. This has been further accelerated by Fonterra adding evidence of recycling as part of their “Co-operative Difference” payment scheme which has seen both AgRecovery and Plasback see significant surges in registrations.

Farm plastics were given additional focus in July 2020 when the Government named Farm Plastics as one of its six priority products. This has ensured that the rural sector now has a responsibility to be environmentally responsive with the plastic products generated within the sector. Following this announcement, the Ministry for the Environment (MFE) advised it would be working with the AgRecovery Foundation to produce the Green-Farm Product Stewardship Scheme.

This document has been designed to create a “one stop shop” to ensure farmers are able to deliver four key plastics streams to local collection centres by 2024. The proposal recommends that these services will be free to customers with any cost incurred generated through levies paid by plastic producers.

The Green-Farm Product Stewardship Scheme, which is yet to be accredited by Government, is a positive step for the industry. However, following further critical analysis and using frequency distribution data gathered from surveys of farmers across Taranaki, it has been found that this service alone will not be fit-for-purpose to service the needs of all farmers.

This analysis and data also suggested that both Plasback and AgRecovery have improvements to make in their service delivery to ensure they are meeting the needs of farmers. It is therefore recommended that these improvements alongside a collaborative approach from all providers will need to be delivered before any potential accreditation is approved.

Frequency distribution analysis of the survey data also indicated that farmers would like a choice in their provider, and a desire to feel that their contribution is valued. In order to achieve this the research demonstrated that offering additional profit based providers for greater convenience would see further engagement from farmers.

In addition, having accuracy around the amount of recycling collected on-farm would quantify the contribution an individual farm is making.

The data also found that household waste is an area where very little emphasis is placed, with significant quantities of household recycling currently being burned/buried or placed in “skip bins” due to a lack of convenient services. This is another area that improvements could be made and a recommendation is made in the report to assess the feasibility of “on-farm recycling stations”.

Finally this report analyses where our current recycling is being processed, whether this is sustainable at its current levels, and if it can sustain an inevitable increase from greater farmer compliance. This report concludes that currently up to 80% of our farm plastics are sent overseas and whilst we are utilising some of this product in New Zealand, this is limited to a few manufacturing companies. In order to be more environmentally responsive in future we need to deal with recycling internally and therefore greater sector and government collaboration is required to assist businesses within New Zealand.

Following the information gained from this report the following recommendations are made:

Establish An Accredited Inclusive Product Stewardship Scheme

1. The current Green-Farm Product Stewardship Scheme proposed by the AgRecovery Foundation is a great initial concept, however it requires further development before any potential accreditation is granted from the Ministry for the Environment.

The “One-Stop Shop” solution is a positive one for the rural industry, however, needs to be more inclusive of other providers including Plasback, for its ultimate success. The proposed scheme needs to better acknowledge the work that is already occurring within the waste sector and utilise these providers in any future scheme. Once these necessary amendments are made the proposal needs to be accredited and operational as projected, in 2024.

Utilise Local Service Providers

2. That local services are required to complement the Green-Farm Product Stewardship Scheme proposal which will both provide additional options for farmers, and service additional waste streams. These services could include on-farm collection as a user pay service that allows for greater convenience to farmers to ensure waste removal and improve recycling practices.

Farmers need the ability to choose the most convenient practice to meet their business needs and one solution will not meet this requirement.

Collection of On-Farm Recycling Levels

3. That volumes of waste and recycling collected needs to be recorded and collated at a farm level. This would allow farmers to accurately record the increased efforts that they are making and to hold those to account who are not making the required effort. This would also allow farmers to provide more accurate statistics across the complete rural sector.

Currently we are not recording this information as accurately as we could. Farmers need to know the difference they are making so showing key individual farm stats as to levels of recycling will be crucial to any future success.

Enhance Government Collaboration

4. That government needs to enhance the work it is doing alongside current businesses within New Zealand who are attempting to use recycling waste and to look to support and develop companies who are trying to operate in New Zealand. Currently up to 80% of our plastic recycling goes offshore to be processed and we therefore need to develop further businesses within New Zealand to service more of our own recycling.

Many of the products that are created from plastic waste are not high value therefore government assistance will be required to ensure companies are able to process these plastics and remain financially sustainable.

Source: ruralleaders.co.nz

Brazil’s Minister of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply, Marco Montes, told this week’s National Dairy Forum that Brazil can be the world’s biggest supplier of dairy products, the way it currently is for soya, coffee and beef. His comments, carried in several Brazilian media outlets, referred to achieving this objective as the country has everything required to do so.

Brazil’s Minister of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply, Marco Montes, told this week’s National Dairy Forum that Brazil can be the world’s biggest supplier of dairy products, the way it currently is for soya, coffee and beef. His comments, carried in several Brazilian media outlets, referred to achieving this objective as the country has everything required to do so.

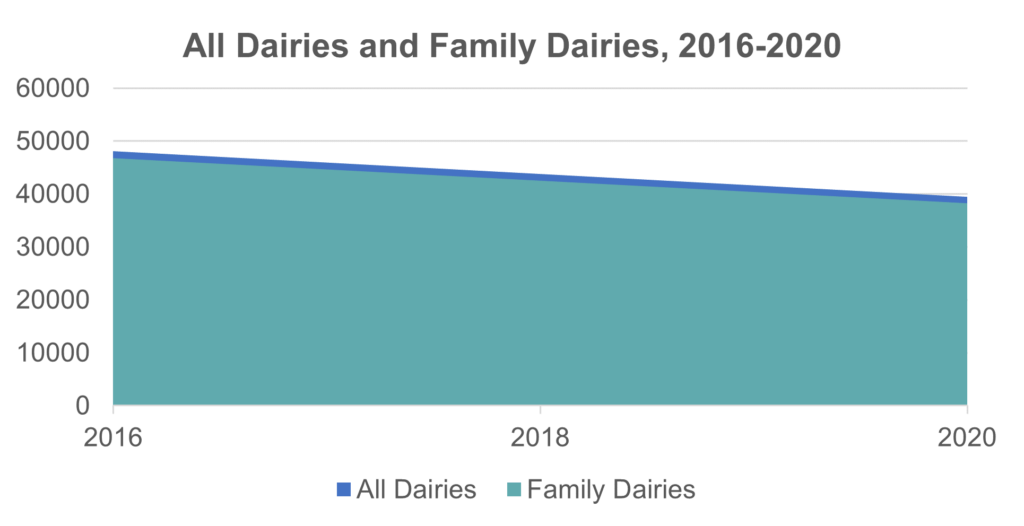

-Jul-07-2022-09-43-46-00-PM.jpg?width=544&name=Chart1%20(2)-Jul-07-2022-09-43-46-00-PM.jpg)

-Jul-07-2022-09-44-41-07-PM.jpg?width=554&name=Chart2%20(2)-Jul-07-2022-09-44-41-07-PM.jpg)

-Jul-07-2022-09-45-25-12-PM.jpg?width=554&name=Chart3%20(2)-Jul-07-2022-09-45-25-12-PM.jpg)