Heat and drought are putting dangerous stress on dairy cows all over the world. This is causing them to stop making milk, which threatens the long-term supply of everything from butter to baby formula.

This year, Australia, a major exporter, is expected to lose nearly 500,000 metric tonnes of dairy as farmers leave the business after years of heat waves making it hard for them to make a living. Small farmers in India are thinking about buying cooling equipment that they would have to save up for. Producers in France had to stop making one type of high-quality cheese because grass-fed cows had nowhere to graze because the fields were too dry.

FRANCE-WEATHER-AGRICULTURE-HEAT

Dairy cows in Saint-Martin-en-Haut, France, during a heat wave in July.

Extreme weather caused by climate change is making some of the world’s biggest milk-producing areas less suitable for these animals: When it’s very hot, cows don’t produce as much milk, and when it’s dry, the grass and other crops they eat dry up, making the problem even worse.

Some scientists think that climate change will cost the dairy industry in the US alone $2.2 billion per year by the end of the century. This is a big hit for an industry that already has trouble making money. One study says that the dairy and meat industries will lose $39.94 billion per year to heat stress by the same date if greenhouse gas emissions stay high.

At the same time, the demand for dairy products is growing because the middle class is growing in many developing countries. However, policies meant to help the environment are discouraging farmers in some areas from increasing their production. This collision could lead to higher prices and shortages of things like cream cheese and yoghurt that are on most grocery lists.

Milk Prices Go Up

Over time, prices for milk and other goods are going up.

FAO of the UN

“Climate change makes your supply more volatile or changeable, which can make it harder to get enough food,” said Mary Ledman, a global dairy strategist at Rabobank.

Cows Under Stress

Extreme heat is making cows uncomfortable and putting the world’s dairy supply at risk.

On Tom Barcellos’s farm, fans and misting machines keep the cattle cool.

Eric Thayer/Bloomberg is the photographer.

Even though dairy farmers spend a lot of money to keep their herds cool, the heat still affects them.

Tom Barcellos has been raising and milking cows on his farm in Tipton, California, for 45 years. His farm has a complicated cooling system. It has fans and machines that mist the air, and it even takes into account the direction of the wind. But he thinks that warm nights can slow down work.

Barcellos, who has 1,800 cows, said, “If you have higher temperatures in the evening and it’s a little more stressful on the cows, you could lose 15% or even 20% in the worst case.”

Extreme heat is making cows uncomfortable and putting the world’s dairy supply at risk.

Tom Barcellos

Eric Thayer/Bloomberg is the photographer.

On the other side of the world, in the western Indian state of Gujarat, Sharad Bhai Harendra Bhai Pandya and his brother have more than 40 cows.

Pandya keeps his cattle in a shed that has a fogger system that pumps water into it and turns it into mist. But even though it’s so hot in the summer, milk production at his farm drops by more than 30%.

If temperatures keep going up, more farmers will likely have to deal with this for longer periods of time. That makes it hard to decide how to invest.

The India Dairy Is in Danger

Ranu Bhai Bharvad’s farm.

Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg is the photographer.

Ranu Bhai Bharvad is a dairy farmer in India, but he doesn’t even have a place for his 35 animals to stay. His cattle only have a neem tree to protect them from the heat.

“I can’t afford to build a shed for my cows,” said Bharvad, whose farm helps him support a family of 15 people.

India is by far the biggest milk producer in the world. Tens of millions of small farmers with only a few animals each make up the majority of India’s milk production.

Amul Dairy, which buys milk from Bharvad and other farmers like him, is taking steps to protect supply in response to the difficult conditions.

“During the winter, when production is higher, we save extra milk in the form of powder in case we don’t have enough during the summer,” said RS Sodhi, the managing director of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd., which owns the Amul brand.

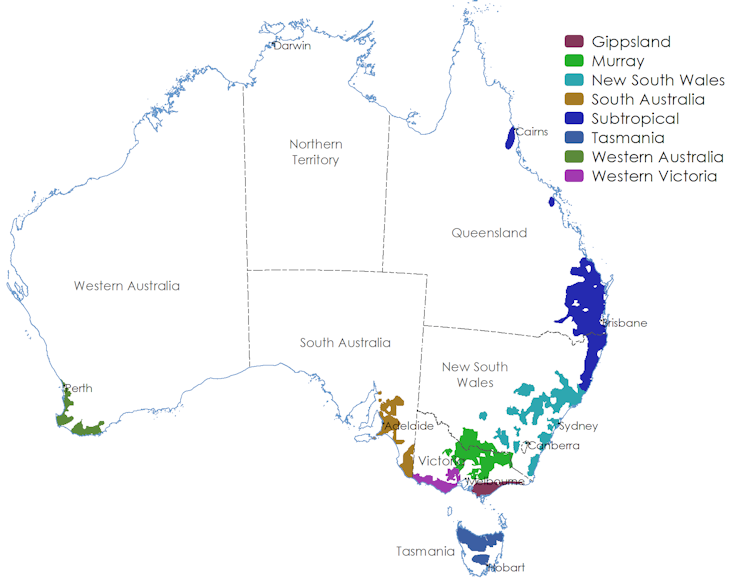

Drought in Australia

The Threat of Tariffs and Dairy Farming in Victoria

In Gippsland, Australia, in the year 2020, milk from Friesian cows goes into a holding vat at a dairy farm.

Carla Gottgens/Bloomberg is the photographer.

Australia, which is the driest inhabited continent on Earth, shows how the dairy industry could fail around the world if climate change gets worse.

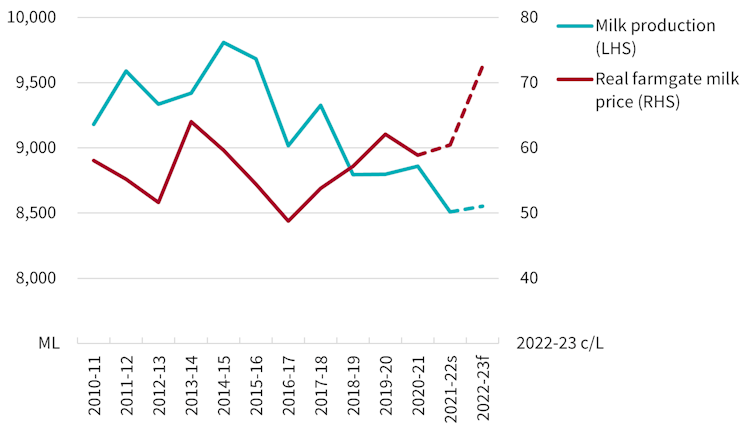

The country used to be a big player in the business, but milk production has gone down sharply, and its share of the global dairy trade has dropped from 16% in the 1990s to around 6% in 2018.

Extreme heat waves, like a drought that lasted from 1997 to 2010 and another that will last from 2017 to 2020, caused the downscaling. The most recent one was the worst on record, and it caused prices for water and feed for cattle to go up, which hurt farmers’ bottom lines. Because business was hard, a lot of people left the industry. From 1980 to 2020, the number of dairy farms in Australia dropped by almost 75%.

Fewer Farms

In the last 40 years, there have been a lot less dairy farms in Australia.

Source: Authorities in Australia in charge of milk

Note: The year 2020 is just a guess. Year shows the end date for a time period that began in the year before.

Now, dairy farmers still have to worry about bad weather, but they also have to deal with new problems that are making them want to quit. The US Department of Agriculture says that Australia’s milk production will drop by more than 4% to 8.6 million metric tonnes in 2022.

The USDA says that this is due to dry conditions in key milk-producing areas as well as problems caused by a lack of workers. For example, some farmers have decided to switch to beef cattle production, which requires less work.

NZEALAND-AGRICULTURE-CLIMATE-TAX

In August, a dairy farm near Cambridge, New Zealand, had cows in a paddock.

Government policies could also end up putting a damper on dairy production around the world. By 2025, farmers in neighbouring New Zealand, which exports more milk than any other country, will have to pay a tax on agricultural emissions. Even though dairy farmers have done a lot to reduce their emissions, they still put out a lot of greenhouse gases because they have to produce manure, fertiliser, and feed. Farm groups are worried that the tax could make dairy farmers use their land for other things, like forestry or something else.

French Cheese

Some products are already harder to find because of the problems dairy farmers are having. This year, France is not making Salers, a type of high-quality cheese. It must be made with milk from grass-fed cows, which is hard to do when pastures are being destroyed by a heat wave like this year’s.

FRANCE-WEATHER-AGRICULTURE-HEAT

In July, dairy cows on a farm in Vire-en-Champagne, France, cool off under water atomizers.

Even though not having fancy cheese isn’t a big deal, problems with production could have a bigger effect on the market when temperatures are very high.

Nate Donnay, director of dairy market insight at StoneX Group Inc., said, “If you look out five to fifteen years, it’s likely that production will reach a peak and then level off in places where there isn’t enough water.” “In the next 15 to 30 years, production could start to go down in those areas.”

All of this could cause prices to go up or even cause some dairy products to run out.

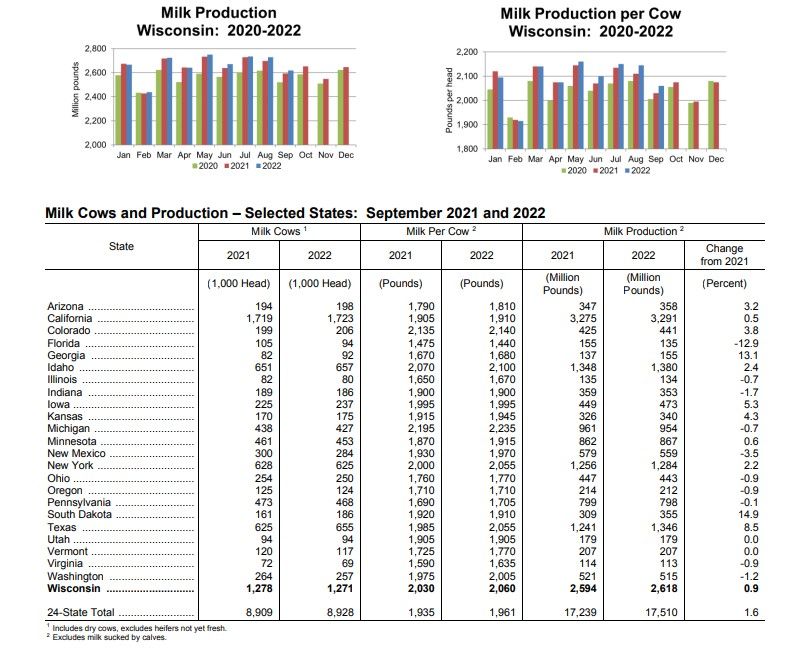

Melvin Medeiros is a farmer in California, which makes more milk than any other state in the US. He says that extreme weather is likely to change how farming works in his state over the next ten years. He thinks that because the government isn’t doing anything, there will be fewer cows and less land that can be used for farming.

Leaders in Dairy

California makes more milk than any other state in the US.

Source: Calculations by the USDA, NASS, and the USDA, Economic Research Service.

“We haven’t done anything about a problem that’s been going on for more than 50 years,” said Medeiros. “Now that we’re in a tight spot, we have no choice but to cut back on production or do something else to fix the problem.”

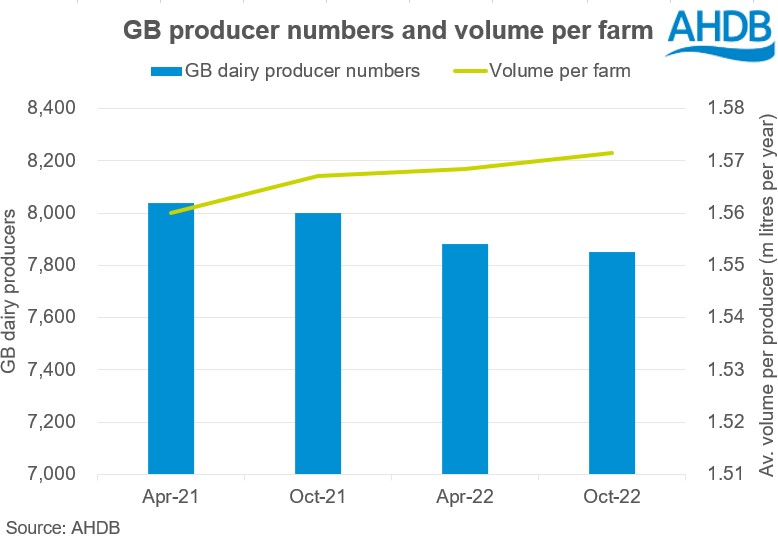

.png?width=554&name=Chart1.svg%20(2).png)

-Oct-05-2022-07-14-12-07-PM.jpg?width=554&name=Chart2%20(2)-Oct-05-2022-07-14-12-07-PM.jpg)

-Oct-05-2022-07-15-24-30-PM.jpg?width=554&name=Chart3%20(2)-Oct-05-2022-07-15-24-30-PM.jpg)