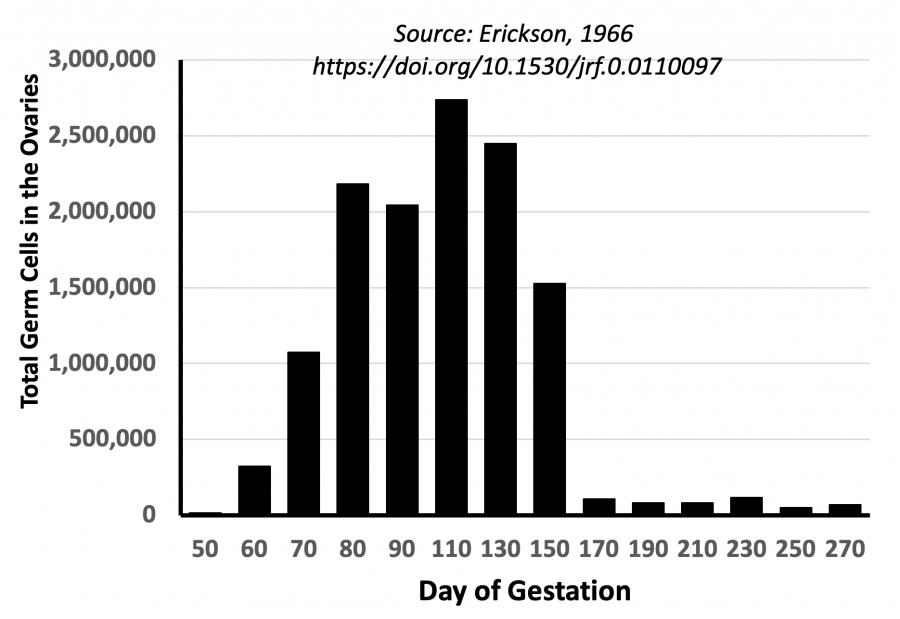

Before answering this question, we need to understand how follicles are formed and what they do. Follicles are the final stage in which germ cells (oocytes or “eggs”) reside before they are ovulated for fertilization by sperm. There is a long history of cattle research in this area, and one of the most important findings was by B.H. Erickson in 1966 (Figure 1). He found that the greatest number of germ cells in ovaries occurred during the fetal stage. At the peak, there were more than 2.5 million germ cells in the ovaries of fetuses. The number of germ cells or follicles then declines throughout life. Importantly, heifers and cows with more ultrasound detectable follicles stay in herds longer. Herd life is a key component of profitability.

Figure 1. Number of germ cells in bovine fetuses during gestation.

Follicle development.

Germ cells are the foundational cells that develop into follicles. A germ cell is an oocyte or egg that will eventually be surrounded by other cells to form a microscopic follicle that will continue to grow until it can be monitored by modern ultrasound devices. As shown in Figure 1, most of the germ cells are depleted before the calf is born, but the newborn calf will still have up to hundreds of thousands of follicles for its future.

Small batches of follicles grow regularly in waves during the late fetal stage, and this continues throughout the heifer or cow’s life. Before puberty, it is possible to aspirate oocytes from the follicles of young heifers, and these can be fertilized in vitro to produce embryos that are then transferred into recipients that have reached puberty.

Once a heifer reaches puberty, generally one follicle will ovulate an unfertilized egg into the oviduct about 24 to 30 hours after onset of estrus. If mated or inseminated, most of these newly released oocytes will be fertilized.

In cyclic heifers and cows, batches of follicles develop to detectable sizes in waves that occur 2 or 3 times during each estrous cycle. Longer estrous cycles are more likely to have 3 waves and shorter cycles are more likely to have 2 waves. One can monitor these waves by daily or twice-daily ultrasound detection, and if the animal is monitored several times daily it is easy to monitor the dominant follicle, which will surpass its cohorts in size before it ovulates.

Postpartum cows that are not yet cycling may show irregular patterns of follicle growth. The ovaries may be “small and smooth” without recurring sizable follicles, or there may be a large persistent follicle that is not accompanied by several normal-sized follicles. This is influenced by postpartum uterine function as well as energy balance.

Why does the number of follicles matter?

If one uses ultrasound technologies to monitor the number of follicles on both ovaries of heifers and cows, it will be found that there is about a 7-fold difference among animals. Nevertheless, the number for each animal is highly repeatable (0.95) https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.104.036277 .

Various research studies have provided evidence that heifers or cows with more ultrasound-detected follicles will stay in the herd longer. Cattle with more follicles respond better to superovulation or oocyte retrieval.

Would monitoring the number of follicles lead to more fertile longer-lived cattle?

Maybe it is time to start monitoring follicle numbers in heifers and cows to determine if there is a genetic basis for the different patterns we see. Heifers with lower numbers of follicles may have lower reproductive life in the herd.

Like any new monitoring technology, there must be some standard practices so that data from different herds are comparable. Monitoring follicle numbers may be easier than one might think. Multiple studies with beef cattle have shown that heifers can be monitored by using ultrasound technologies to count the number of follicles, and this does not have to be done on a specific day of an estrous cycle. This makes it much simpler to collect data at any time once a heifer reaches about 12-14 months of age.

From a practical standpoint, it would be beneficial if we could identify heifers that are more likely to stay in the cow herd longer by monitoring the number of follicles present when these heifers are 12 to 14 months of age. It is too early to know whether this would be valuable in most herds until we have data from many herds across many locations.

The process may be simple. Heifers would be screened by ultrasound evaluation of their ovaries at about 12 to 14 months of age, around the time they are reaching puberty. Subsequently, it would be necessary to correlate the number of follicles counted with important traits such as milk yield, conception rates and herd life. This opportunity, like many others in our dairy selection programs, will only become useful if we find meaningful relationships that are related to herd life and profitability.

Get original “Bullvine” content sent straight to your email inbox for free.

[related-posts-thumbnails]